How Do You Know If Moonshine Mash Is Bad: Expert Tips to Spot Problems

Key Takeaways

- Visual inspections are crucial for detecting bad moonshine mash – look for unusual colors, mold growth, or strange films on the surface.

- A properly fermenting mash should smell yeasty or fruity, while foul, putrid, or chemical odors indicate contamination.

- Hydrometer readings that show incomplete fermentation despite time passing can signal problems with your mash.

- Proper sanitation during preparation and an airlock system are your best defenses against mash contamination.

- American Home Distillers recommends immediate disposal of any mash showing clear signs of contamination to avoid health risks.

Knowing when your moonshine mash has gone bad can save you time, resources, and potentially protect you from serious health hazards. While home distillation requires practice and knowledge, one of the most critical skills is identifying when fermentation has gone awry.

American Home Distillers is committed to educating home distillers about safe practices, including how to spot problems in your mash before they become dangerous. Properly identifying bad mash is an essential skill that separates novice distillers from those with experience and knowledge.

The Critical Signs Your Moonshine Mash Has Gone Bad

“Basic Moonshine Mash Recipe” from www.whiskeystillpro.com and used with no modifications.

Fermentation is a delicate biological process that can easily go wrong without proper attention to detail. A bad mash doesn’t just mean a poor-tasting final product—it can potentially create harmful compounds that shouldn’t be consumed. Recognizing the warning signs early can help you decide whether to proceed with distillation or start fresh with a new batch.

Safety First: Why Bad Mash Detection Matters

When fermentation goes wrong, your mash can develop harmful bacteria, wild yeasts, or molds that produce undesirable compounds. These contaminants can create off-flavors at best and dangerous substances at worst. While distillation will remove many contaminants, some compounds can still make it through the process or affect the quality of your final product. Additionally, working with contaminated mash can introduce these unwanted elements into your equipment, potentially affecting future batches.

Common Causes of Mash Contamination

Understanding what causes mash to go bad helps you prevent problems before they start. Most issues stem from poor sanitation practices, improper fermentation conditions, or mistakes in the mash preparation process. Introducing wild yeasts or bacteria from unclean equipment is the most common culprit.

- Inadequate sanitation of equipment and fermenting vessels

- Incorrect fermentation temperatures (too high or too low)

- Poor-quality ingredients or water with contaminants

- Improper sealing allowing outside air to enter the fermentation vessel

- Cross-contamination from other fermentation projects

The fermentation environment plays a crucial role in determining whether your mash will develop properly or become contaminated. Too much exposure to oxygen after initial fermentation begins can lead to oxidation and encourage the growth of acetic acid bacteria, which turn alcohol into vinegar. Similarly, fluctuating temperatures can stress your yeast, making them perform poorly and allowing other microorganisms to take hold.

Visual Red Flags That Spell Trouble

“Flag Red Warning Stock Illustrations …” from www.dreamstime.com and used with no modifications.

Your eyes are one of your most valuable tools for detecting problems with your mash. A healthy mash will have a consistent appearance appropriate to its ingredients, while problematic fermentations often display visible warning signs that something has gone wrong. Regular visual inspection throughout the fermentation process is essential for catching issues early.

Abnormal Colors That Signal Contamination

A properly fermenting mash should maintain a relatively consistent color appropriate to its ingredients. For grain mashes, this typically means a tan to brown coloration, while fruit mashes will reflect the fruits used. Any unexpected color changes—especially to green, blue, black, or bright white—typically indicate contamination. Particularly concerning are blue-green hues, which often signal the presence of molds that can produce mycotoxins. Pink or purple discolorations may indicate certain bacterial infections that can produce off-flavors and potentially harmful compounds.

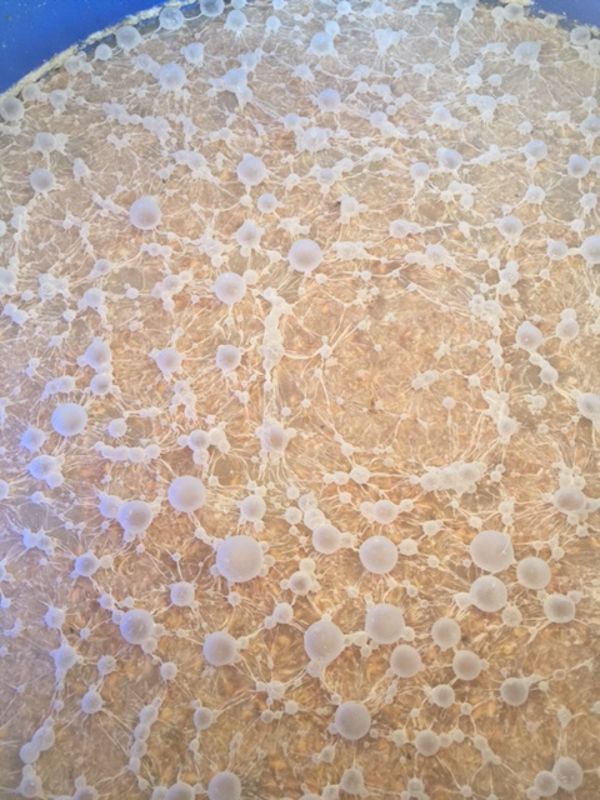

Mold Growth and What It Looks Like

Mold in your mash is one of the most obvious and concerning signs of contamination. Healthy fermentation should never produce mold growth. Mold typically appears as fuzzy or powdery patches that can be white, green, black, or blue in color. These patches often start small but can quickly spread across the surface of your mash. Any sign of mold means your mash is contaminated and should not be used for distillation.

Particularly dangerous are black and blue-green molds, which can produce mycotoxins that may survive the distillation process. White mold might be confused with normal yeast activity, but yeast forms a more uniform, creamy layer rather than fuzzy spots. If you’re unsure whether what you’re seeing is mold or yeast, err on the side of caution and consider the batch compromised.

Strange Films or Layers on Top

A healthy fermentation will typically have some foam or a thin, creamy layer of yeast on top. However, problematic films have distinctive characteristics that set them apart. Watch for slick, oily-looking films that form a complete layer across the surface, particularly those with rainbow-like sheens. Pellicles—tough, leathery films that form on top of the mash—indicate wild yeast or bacterial contamination, most commonly from Brettanomyces or Acetobacter.

These bacterial films are particularly concerning because they can turn your alcohol into vinegar or produce other unwanted flavors and compounds. While some craft brewers intentionally introduce these bacteria for sour beers, they’re generally unwelcome in moonshine production where clean fermentation is the goal.

Unusual Sediment or Particles

Normal fermentation produces sediment as yeast cells settle out, but this sediment should generally be uniform in color and consistency. Unusual floating particles, especially those that appear stringy, slimy, or gelatinous, are warning signs. These formations, sometimes called “ropiness,” indicate bacterial infection that can produce off-flavors and potentially harmful byproducts.

Another concerning sign is sediment that appears unusually chunky or has distinct colors different from your mash ingredients. This can indicate that unwanted microorganisms have formed colonies within your mash. In extreme cases, you might see what looks like “strands” or “chains” connecting through the liquid—this is a clear indication of bacterial contamination.

The Nose Knows: Smell Tests for Bad Mash

“Amazon.com : Bad Breath Tester Odor …” from www.amazon.com and used with no modifications.

Your sense of smell is perhaps the most reliable tool for detecting problems with your mash. The aroma of a healthy fermentation should change predictably over time, moving from the sweet smell of your initial ingredients to the more complex aromas of active fermentation. Any unexpected or unpleasant odors suggest something has gone wrong with the fermentation process.

Normal Fermentation Smells vs. Warning Odors

A properly fermenting mash will produce distinct aromas that evolve as fermentation progresses. Initially, you’ll smell the sweet aroma of your base ingredients mixed with the bread-like smell of active yeast. As fermentation continues, these aromas will develop into a more complex, slightly alcoholic smell with fruity or spicy notes, depending on your yeast strain and ingredients. These smells, while strong, should never be offensive or make you recoil.

Warning odors, by contrast, are unmistakably unpleasant and often cause an immediate negative reaction. Any smell described as putrid, rotten, fecal, or reminiscent of garbage indicates serious contamination by harmful bacteria. These odors signal that your mash has become a breeding ground for unwanted microorganisms, and continuing with such a batch could result in a product that’s not only unpalatable but potentially dangerous. For those interested in the traditional corn-based moonshine recipe, ensuring the mash is free from these odors is crucial for a safe and quality product.

Sour, Vinegar-Like Scents

One of the most common problem odors is a sharp, acidic smell similar to vinegar. This occurs when acetobacter bacteria convert the alcohol in your mash into acetic acid. While a slight tanginess can be present in some fermentations, a strong vinegar smell means your mash has been exposed to too much oxygen, allowing these bacteria to thrive. Once this process starts, it’s difficult to stop, and it will continue to convert more alcohol to vinegar over time. For more insights on this, check out this discussion on mash fermentation issues.

Another acidic smell to watch for is a sour milk or yogurt-like aroma, which indicates lactic acid bacteria have taken hold. While these bacteria aren’t necessarily harmful, they’ll compete with your yeast for resources and can significantly alter the flavor profile of your final product. In moonshine production, where clean neutral spirits are often the goal, these flavors are typically considered defects.

Chemical or Solvent Odors to Watch For

Chemical smells resembling nail polish remover, paint thinner, or model glue indicate the presence of excessive esters or solvents in your mash. Small amounts of these compounds naturally occur during fermentation, but overwhelming chemical aromas suggest something has gone seriously wrong. These smells often indicate stressed yeast producing excess fusel alcohols or acetone, which can lead to harsh flavors and potential health concerns in the final product.

Particularly alarming are any aromas resembling rotten eggs, sulfur, or striking matches. While a small amount of sulfur is normal in early fermentation (especially with certain yeast strains), persistent or strong sulfur smells can indicate bacterial contamination or yeast struggling due to nutrient deficiencies. These compounds can carry over into your distillate, creating unpleasant flavors that are difficult to remove.

Fermentation Problems You Can Hear and Feel

“A Complete Guide to Fermenting Grains …” from svasthaayurveda.com and used with no modifications.

Beyond sight and smell, your mash can communicate problems through other sensory cues. The sounds of active fermentation, the texture of the mash, and how it behaves when disturbed can all provide valuable information about whether fermentation is proceeding normally or has encountered problems. Developing sensitivity to these subtle signs can help you catch issues that might not be immediately visible.

Lack of Bubbling Activity

Healthy fermentation produces carbon dioxide, creating a noticeable bubbling or fizzing sound in the early to middle stages. This activity should begin within 24-48 hours of pitching your yeast and continue steadily for several days before gradually slowing. If you don’t hear or see any bubbling activity after two days, your fermentation may have failed to start properly. Similarly, if bubbling stops abruptly much earlier than expected, something may have killed or inhibited your yeast.

Unusual Texture Changes

The texture of your mash should change in predictable ways as fermentation progresses. Initially, it might be thick or viscous depending on your ingredients, but it should become thinner as fermentation breaks down sugars and starches. A mash that becomes unusually slimy, gelatinous, or stringy when disturbed indicates bacterial contamination. Such texture changes are often accompanied by visual and olfactory warning signs, but sometimes the texture change comes first.

Another texture-related warning sign is mash that feels unusually “dead” or still when stirred. Healthy mash should have a certain liveliness to it during active fermentation, with light effervescence when disturbed. If your mash feels flat and lifeless before fermentation should be complete, it may indicate that your yeast has stopped working prematurely or that something has killed the fermentation process.

Scientific Tests to Confirm Mash Quality

“How to Make Moonshine: Easy Step-by …” from homebrewacademy.com and used with no modifications.

While sensory observations are valuable, sometimes you need more objective measurements to determine if your mash is developing properly. Simple scientific tests can provide concrete data about your fermentation’s progress and health, helping you make informed decisions about when to distill or whether to discard a questionable batch.

Hydrometer Readings That Indicate Problems

A hydrometer measures the density of your mash, indicating how much sugar has been converted to alcohol. Taking regular hydrometer readings throughout fermentation allows you to track progress and identify problems early. The specific gravity should steadily decrease as fermentation converts sugars to alcohol, eventually stabilizing when fermentation is complete.

Readings that stall at a higher-than-expected gravity despite adequate time suggest your yeast has stopped working prematurely. This could indicate contamination, poor yeast health, or inadequate nutrients. Similarly, gravity readings that drop far faster than expected might indicate bacterial infection rather than normal yeast activity, as some bacteria consume sugars more rapidly than yeast but produce undesirable byproducts.

If your gravity reading hasn’t changed for 2-3 consecutive days and is within the expected final range for your recipe, fermentation is likely complete. However, if it stalls at a much higher gravity than expected, something has interfered with your yeast’s ability to complete its work.

pH Testing for Contamination

The pH of your mash provides another objective measurement of fermentation health. Healthy fermentation typically maintains a pH between 4.0 and 5.5, creating an environment hospitable to yeast but challenging for many unwanted bacteria. A pH that drops below 3.8 may indicate contamination with acid-producing bacteria, while a pH that rises above 5.5 could suggest alkaline-producing contamination.

Monitoring pH throughout fermentation can help you catch problems before they become severe. A sudden shift in pH without explanation is always a red flag. Inexpensive pH strips or digital pH meters make this testing simple and accessible for home distillers, providing valuable data about your fermentation’s health. For those interested in exploring more about moonshine, check out this traditional corn-based moonshine recipe.

Timing Issues: When Fermentation Goes Wrong

“Appalachian Moonshine – Potential …” from www.stilldragon.org and used with no modifications.

The timeline of fermentation offers important clues about mash health. Fermentation should follow a relatively predictable pattern of activity, and deviations from this pattern often signal problems. Understanding what normal timing looks like helps you recognize when things aren’t proceeding as they should.

Stalled Fermentation Signs

A stalled fermentation occurs when yeast activity stops before consuming all available sugars. This often happens because of nutrient deficiencies, temperature fluctuations, or alcohol levels becoming too high for the yeast strain you’re using. Signs include lack of visible activity (bubbling, foaming) despite a hydrometer showing significant remaining sugars.

Stalled fermentations are particularly vulnerable to contamination, as inactive yeast leaves the environment open for other microorganisms to take hold. If your fermentation stalls, first try rousing the yeast by gently stirring the mash or slightly raising the temperature within the yeast’s optimal range. If these efforts fail to restart activity within 24-48 hours, you may need to add fresh, active yeast that’s tolerant of higher alcohol environments. For more details on yeast usage, check out how much yeast is needed for a 5-gallon moonshine mash.

Over-Fermentation Problems

While less common than stalled fermentation, over-fermentation can also indicate problems. This typically occurs when fermentation continues beyond the expected timeframe, potentially fermenting compounds that weren’t intended to be fermented. Signs include gravity readings lower than expected for your recipe and extended periods of activity.

Over-fermentation often happens when wild yeasts or certain bacteria have contaminated your mash. These organisms can ferment sugars that brewing yeasts cannot, resulting in excessively dry final products with unpleasant flavors. Extended fermentation can also increase the production of fusel alcohols and other undesirable compounds that contribute harsh flavors and increased hangover effects.

Can You Fix a Contaminated Mash?

“Can We Fix A Ruined Mash? – YouTube” from www.youtube.com and used with no modifications.

When you’ve invested time and resources into a mash, discovering contamination can be disheartening. The natural question becomes whether you can salvage the batch or if you’re better off starting fresh. The answer depends on the type and severity of contamination, as well as your tolerance for risk.

When to Attempt Rescue vs. When to Dump

Minor issues caught early sometimes can be addressed. If fermentation has just begun to slow or show subtle signs of problems, interventions like adjusting pH, adding yeast nutrients, or pitching fresh yeast might help. However, these measures are preventative rather than curative—they work best before contamination becomes established.

Clear signs of contamination—mold growth, foul odors, or slimy textures—indicate a batch that should be discarded. No amount of intervention will make these batches safe or palatable, and attempting to distill severely contaminated mash risks carrying over harmful compounds and contaminating your still. Remember that many contaminants produce byproducts that can survive distillation, potentially making your final product unsafe. For more information on moonshine production, learn about the three main parts of a still and how they function.

Safe Recovery Techniques

For mashes with minor issues like slightly slowed fermentation or mild off-odors that aren’t clearly foul, a few interventions might help. Adding a small amount of acid (like citric acid) to lower the pH can create an environment more hostile to bacteria while remaining suitable for yeast. Similarly, raising the temperature slightly within the yeast’s optimal range can reinvigorate fermentation, helping the yeast outcompete potential contaminants.

Prevention: Keeping Your Moonshine Mash Healthy

“How to Make Moonshine Mash: 13 Steps …” from www.wikihow.com and used with no modifications.

The best approach to contamination is preventing it from occurring in the first place. Proper preparation, equipment, and monitoring practices dramatically reduce the risk of developing problems with your mash. By establishing good habits from the start, you can save yourself the disappointment of discarding ruined batches.

Proper Sanitation Practices

Sanitation is the cornerstone of successful fermentation and the single most important factor in preventing contamination. Before your mash even touches a fermenter, every surface and tool that will contact it must be thoroughly cleaned and sanitized. Clean equipment first with hot water and appropriate cleaners to remove any visible residue or organic matter.

After cleaning, sanitize everything with a food-grade sanitizer like Star San or diluted bleach solution (making sure to rinse thoroughly if using bleach). Pay special attention to valves, airlock components, and other areas that can harbor bacteria. Remember that cleaning and sanitizing are different processes—cleaning removes visible dirt, while sanitizing kills microorganisms. For those interested in moonshine production, understanding the traditional corn-based moonshine recipe can be a valuable resource.

Develop a systematic sanitation routine and follow it religiously for every batch. This isn’t an area where shortcuts pay off; thorough sanitation practices are your first and most important defense against contamination. For those new to moonshine, understanding the legality of stills in the US can also be crucial in ensuring safe and compliant production.

- Clean and sanitize all equipment before and after use

- Use food-grade sanitizers at appropriate concentrations

- Pay special attention to small parts, seals, and hard-to-reach areas

- Sanitize hands or wear clean gloves when handling ingredients

- Keep pets and other potential contamination sources away from your workspace

Ideal Storage Conditions

Where and how you store your fermenting mash significantly impacts its development and vulnerability to contamination. The ideal environment maintains a stable temperature appropriate for your yeast strain, typically between 65-75°F (18-24°C) for most distiller’s yeasts. Temperature fluctuations stress yeast, potentially causing them to slow or stop working, creating opportunities for contaminants to take hold. Consider using a dedicated fermentation chamber or temperature-controlled space if your ambient environment isn’t suitable.

Airlock Usage and Maintenance

An airlock is essential equipment that allows carbon dioxide to escape from your fermenter while preventing outside air (and the microorganisms it carries) from entering. Check your airlock regularly to ensure it contains the proper amount of sanitizing solution and is functioning correctly. Dry airlocks or those that have been siphoned empty due to temperature changes offer no protection against contamination. Similarly, airlocks that become clogged with foam or debris can create pressure problems within your fermenter, potentially forcing the stopper out or causing the vessel to crack.

The Bottom Line on Mash Quality Control

“How To Make Moonshine: A Step By Step Guide” from www.clawhammersupply.com and used with no modifications.

Maintaining vigilance throughout the fermentation process is your best strategy for producing quality moonshine. Regular sensory checks, combined with objective measurements like hydrometer readings and pH tests, provide a comprehensive picture of your mash’s health. Addressing minor issues promptly can prevent them from developing into major problems that ruin your batch.

Remember that fermentation is a biological process, and some variation is normal. Learning to distinguish between typical fermentation characteristics and warning signs comes with experience. When in doubt about a batch’s safety or quality, the prudent approach is to discard it rather than risk producing a potentially harmful product. No batch of moonshine is worth compromising your health or safety. For more insights on fermentation, check out this discussion on mash safety.

The skills required to evaluate mash quality develop over time as you gain experience with different recipes and fermentation conditions. Keep detailed records of each batch, noting observations throughout the process and correlating them with the final product’s qualities. This documentation builds a valuable knowledge base that improves your distilling skills with each batch.

Quick Reference: Bad Mash Warning Signs

Sense Warning Signs Possible Causes Visual Mold growth, unusual colors, slimy films Bacterial/fungal contamination Smell Putrid, vinegar, chemical odors Acetobacter, wild yeast, bacteria Touch Slimy texture, unusual viscosity Bacterial contamination Measurement Stalled gravity, extreme pH changes Stressed yeast, contamination

Frequently Asked Questions

As distillers gain experience, many common questions arise about mash quality and fermentation problems. These frequently asked questions address common concerns and misconceptions about moonshine mash fermentation.

How long can I store my mash before it goes bad?

With proper airlock protection and sanitary conditions, a completed mash can be stored for several weeks or even months before distillation. The key is keeping air exposure minimal and maintaining the airlock. For long-term storage over a month, consider racking (transferring) the mash off the yeast sediment into a clean secondary container to prevent yeast autolysis, which can create off-flavors. Remember that the longer you store your mash, the greater the risk of something going wrong, so distilling promptly after fermentation completes is generally best practice.

Is it safe to taste moonshine mash to check if it’s good?

While commercial brewers often taste fermenting wort to evaluate progress, tasting moonshine mash carries additional risks. Unlike beer mashes that are typically boiled before fermentation, many moonshine mashes aren’t heat-treated, potentially harboring harmful bacteria. If you do choose to taste your mash, use extreme caution and only taste minuscule amounts of mashes that show no visible or olfactory signs of contamination.

A safer approach is to rely on hydrometer readings, pH tests, and sensory observations that don’t involve tasting. These methods provide ample information about your fermentation’s health without the potential risks of consuming contaminated mash.

Can I still distill mash that smells a bit off?

Minor off-aromas that are more “unusual” than outright foul might still produce acceptable distillate, as the distillation process will remove many volatile compounds. However, significantly off-smelling mash should never be distilled. Certain bacteria produce toxic compounds that can survive distillation, and some contaminants can even damage your still. Additionally, distilling contaminated mash often results in low yields and poor-quality spirits, making it a waste of time and energy. When in doubt, it’s always safer to discard suspicious mash and start fresh rather than risk your equipment or health.

What’s the difference between normal yeast activity and contamination?

Normal yeast activity produces a consistent layer of foam or krausen during active fermentation, with a clean, yeasty, or fruity aroma. This foam should be relatively uniform in color and texture. Contamination, by contrast, often appears as irregular patches, unusual colors, or films with inconsistent textures. The smell is the most reliable indicator—yeast produces pleasant bread-like, fruity, or clean alcoholic aromas, while contamination typically creates sharply sour, putrid, or chemical smells that trigger an instinctive aversion.

Do different mash recipes spoil in different ways?

Yes, different mash recipes show contamination in slightly different ways based on their ingredients. Fruit-based mashes tend to be more acidic, providing some natural protection against certain bacteria, but are more susceptible to mold growth on floating fruit pieces. Grain mashes typically have higher pH and are more vulnerable to bacterial infection. Sugar washes, being nutritionally simple, may show stalled fermentation if contaminating organisms consume the nutrients needed by yeast. Learning the specific characteristics of your preferred recipes helps you better identify when something isn’t developing as expected.

The most important skill in home distilling is learning to trust your senses when they tell you something isn’t right. Experience will help you distinguish between normal fermentation variations and genuine problems that require intervention or disposal of the batch.

By maintaining strict sanitation practices, controlling fermentation conditions, and promptly addressing any issues that arise, you’ll significantly improve your success rate with moonshine mash fermentation. For those interested in exploring more, consider trying a traditional corn-based moonshine recipe to further enhance your skills. The reward for this diligence is consistently high-quality spirits that you can enjoy with confidence.

Moonshine, a high-proof distilled spirit, has been a part of American culture for centuries. It is often made in small batches using traditional methods passed down through generations. However, many people are unaware of the legal implications surrounding its production. For those curious about the legality, it’s important to understand whether stills are illegal in the US before embarking on any moonshine-making adventures.