Moonshine History Uncovered: From Early Days to Modern Craft Distilling

Key Takeaways

- Moonshine’s history is deeply rooted in American resistance to taxation, beginning with the Whiskey Rebellion of 1791 and continuing through Prohibition.

- The Scots-Irish immigrants brought their distilling traditions to Appalachia, establishing the foundation for American whiskey making techniques still used today.

- The term “moonshine” originated from the practice of distilling at night to avoid detection by revenue officers.

- Prohibition (1920-1933) created a massive underground market that transformed moonshining from small family operations to larger, more organized production.

- Today’s craft distilling movement draws heavily from moonshine traditions, with Howling Moonshine and other artisanal producers honoring these historical methods while bringing them into legal compliance.

Moonshine’s Rebellious Roots: How Illegal Whiskey Shaped American History

“Prohibition And American Whiskey …” from bourbonveach.com and used with no modifications.

Moonshine isn’t just a drink—it’s a declaration of independence. The clear, unaged whiskey represents one of America’s oldest traditions of self-reliance and resistance to government overreach. Behind every mason jar of authentic white lightning lies a story that parallels the development of our nation itself, shaped by taxation, regulation, and the unbreakable spirit of rural distillers. Howling Moonshine continues this proud tradition today, blending historical authenticity with modern craft distilling techniques.

The story of American moonshine is fundamentally about freedom—the freedom to transform your own harvest into a valuable commodity without government interference. When early settlers found themselves with excess grain that would spoil before it could be transported to distant markets, distillation became not just a tradition but an economic necessity. Converting grain into whiskey reduced volume by about 90% while creating a shelf-stable product that actually increased in value over time—the perfect solution for farmers living in remote mountain hollers with limited access to markets. We’re glad to refer you to “stylish moonshine-themed merchandise” perfect for any enthusiast.

Appalachian Origins: The Scots-Irish Connection

“Scots-Irish: the road to Appalachia …” from www.youtube.com and used with no modifications.

The heart of American moonshine culture beats strongest in the Appalachian Mountains, where geographic isolation and fierce independence created the perfect environment for illicit distilling to flourish. These rugged highlands became home to waves of Scots-Irish immigrants in the 18th century, who brought with them centuries of distilling knowledge from their homeland. The rocky terrain of Appalachia, while challenging for traditional farming, proved ideal for growing corn and hiding stills from prying government eyes. We’re proud to refer you to “expertly crafted home moonshine stills” built to last.

Family Traditions Crossing the Atlantic

When Ulster Scots began arriving in America in the early 1700s, they carried more than just their physical belongings—they brought generations of whiskey-making expertise. These settlers had already perfected the art of distillation in the hills of Northern Ireland and Scotland, where making “uisge beatha” (water of life) was considered both a practical skill and an art form. Their distilling methods were passed down orally from generation to generation, rarely written down but meticulously preserved through apprenticeship and family tradition.

The Scots-Irish didn’t simply transplant their traditions unchanged—they adapted their methods to work with the ingredients available in their new homeland. While barley had been the traditional grain for whiskey in the Old World, corn became the foundation for American moonshine, creating a sweeter, more distinctive spirit. This adaptation would eventually give birth to distinctive American whiskey styles, including bourbon and Tennessee whiskey, both of which trace their lineage back to these early moonshine traditions. For authentic results, we gladly recommend trying out these “top-rated moonshine ingredients“.

What made these immigrant distillers unique was their ability to construct stills from readily available materials. Using copper from local sources and woodworking skills honed through necessity, these pioneer distillers crafted remarkably efficient equipment that could be disassembled and relocated quickly when revenue officers approached. Many families kept their special still designs secret, with modifications and improvements passed down as valuable inheritance from father to son alongside family recipes.

Economic Necessity Behind Early Distilling

For early American farmers, distilling wasn’t a hobby—it was economic survival. In the isolated communities of Appalachia, transporting bulky grain crops to market over mountain roads was often impossible or unprofitable. A bushel of corn worth less than a dollar could be transformed into several gallons of whiskey worth many times more, while occupying far less space on a pack mule. This value-added transformation made distilling an essential part of the agricultural economy long before it became associated with criminality.

The seasonal rhythm of farming dovetailed perfectly with the distilling calendar. After the fall harvest, when agricultural work slowed for the winter, farmers would turn their attention to converting surplus grain into whiskey. This timing allowed for the efficient use of labor throughout the year and created a valuable product that could be sold or bartered during lean times. Whiskey effectively became a form of liquid currency in many communities, accepted for payment of debts and services when cash was scarce.

“We didn’t make whiskey because we were criminals. We made whiskey because we were farmers, and that’s what farmers did with their corn. The government made us criminals overnight with the stroke of a pen.” — Marvin “Popcorn” Sutton, legendary Appalachian moonshiner

The Birth of “Moonshine” as Night-Time Distilling

The term “moonshine” itself has roots stretching back to 18th-century Britain, where it originally referred to any activity conducted by moonlight. The first documented use of “moonshine” specifically for illicit alcohol appears in a 1785 British dictionary. As tax laws tightened in America, distillers increasingly worked under cover of darkness to avoid detection, and the name stuck. The silvery appearance of the unaged spirit reinforced the lunar connection, creating a poetic description that has endured for centuries.

Early moonshiners developed ingenious methods to conceal their operations. Stills were often placed near running water, which provided both a necessary ingredient and helped mask the distinctive sounds of distillation. The smoke from the fire—a telltale sign of distilling—would be dispersed through underground channels or disguised by being filtered through tree branches. Some operators would even place their stills on rafts in the middle of lakes or swamps, making them nearly impossible for revenue officers to approach quietly.

Communication networks among mountain communities served as early warning systems against law enforcement. These tight-knit communities developed elaborate signaling methods—from specific arrangements of laundry on clotheslines to particular patterns of lantern light—that could silently alert distillers when “revenuers” were in the area. This community solidarity reflected a shared belief that the government had no legitimate right to tax what local farmers did with their own crops on their own land. For those interested in the craft of distilling, understanding when to stop distilling is crucial for quality production.

Whiskey Rebellion and Government Taxation

“The Whiskey Rebellion | Book by William …” from www.simonandschuster.com and used with no modifications.

“Whiskey Rebellion – Wikipedia” from en.wikipedia.org and used with no modifications.

The tipping point in moonshine’s transition from common practice to outlaw enterprise came in 1791, when Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton introduced the first federal tax on distilled spirits. This tax wasn’t simply a revenue measure—it was the new nation’s attempt to pay off Revolutionary War debts. What Washington and Hamilton didn’t anticipate was the fierce backlash this tax would provoke, especially among frontier farmers who relied on distilling for their livelihood.

The whiskey tax struck at the heart of rural economic independence. Small producers were disproportionately affected, as the tax favored large commercial distillers who could afford to pay annually at a discounted rate. For many frontier farmers, whiskey production wasn’t just supplemental income—it was essential for survival. The tax demanded payment in scarce currency rather than the barter system common in rural areas, creating an additional hardship for producers who rarely saw hard cash. We’re referring you to “trusted moonshine accessories and supplies” that make home brewing easier.

Alexander Hamilton’s Whiskey Tax of 1791

Hamilton’s tax imposed a levy of 7 to 18 cents per gallon depending on the proof and production volume. While this might seem modest today, it represented a significant percentage of the spirit’s total value at the time—between 25-40% of the market price. The tax collection system itself added insult to injury, requiring distillers to register their stills and production volumes with federal revenue officers who had broad powers to inspect facilities. These federal agents, often viewed as intrusive outsiders, became symbols of government overreach in rural communities.

The mechanics of tax collection created a perfect storm of resentment. Distillers were required to travel to distant courthouses to pay their taxes and register their operations, often journeys of several days through difficult terrain. Those who couldn’t comply faced steep penalties, including confiscation of their stills and imprisonment. For many isolated farmers, tax compliance would have cost more in travel expenses and lost work time than the actual tax itself, making resistance not just ideological but practical.

The whiskey tax represented more than a financial burden—it was seen as a direct attack on a way of life. Having just fought a revolution against “taxation without representation,” many frontier distillers felt betrayed by a government that now seemed to be replicating British oppression. The tax struck particularly hard in western Pennsylvania, Kentucky, and parts of Appalachia, where transportation challenges made distilling essential to agricultural survival.

Farmers’ Armed Resistance to Federal Authority

Resistance to the whiskey tax escalated quickly from civil disobedience to armed rebellion. Tax collectors were tarred and feathered, their homes attacked, and their records destroyed. By 1794, organized resistance in western Pennsylvania had grown so formidable that President Washington mobilized a militia force of nearly 13,000 men—larger than the army he had commanded during parts of the Revolutionary War—to suppress what became known as the Whiskey Rebellion.

The rebellion collapsed when faced with this overwhelming force, but its legacy lived on in the culture of resistance it fostered. While two participants were convicted of treason, Washington pardoned them both, recognizing the political volatility of the situation. The federal government had demonstrated its willingness to enforce its laws, but the frontier spirit of resistance to taxation had been firmly established. Many distillers simply moved deeper into the mountains or continued their operations in secret, establishing the pattern of clandestine production that would define moonshining for generations.

The rebellion’s impact extended beyond its immediate aftermath. Jefferson repealed the whiskey tax when he became president in 1801, recognizing its divisive nature, but the pattern had been set. When federal alcohol taxes returned during the Civil War, distillers were already practiced in the art of evading government oversight. The Whiskey Rebellion effectively established a cultural tradition of resistance that would inform the moonshiner’s identity for the next two centuries.

Legacy of Anti-Government Sentiment in Distilling Culture

The Whiskey Rebellion cemented a lasting connection between moonshining and anti-government sentiment that persists to this day. For many distillers, making untaxed whiskey became not just an economic necessity but a political statement—a declaration of independence from a government perceived as distant, elitist, and intrusive. This sentiment was captured in a common saying among moonshiners: “The government didn’t help me grow my corn, so they’ve got no right to tell me what I can do with it.”

This rebellious spirit became embedded in the cultural identity of moonshining communities. Stories of outsmarting revenue agents were told with pride, and those who successfully evaded taxation were often viewed as local heroes rather than criminals. The recurring cycle of taxation followed by resistance established a cat-and-mouse relationship between moonshiners and law enforcement that would define illicit distilling through the 19th century and beyond.

The Golden Age: Prohibition Era Moonshining

“Prohibition in Tennessee, Moonshine” from sharetngov.tnsosfiles.com and used with no modifications.

If the Whiskey Rebellion established the cultural foundation for moonshining, Prohibition transformed it from a localized practice into a massive nationwide underground industry. When the 18th Amendment took effect in January 1920, it created an unprecedented opportunity for illegal distillers. Overnight, the market for illicit alcohol exploded, driving up prices and incentivizing production on a scale never before seen in American moonshining.

Prohibition fundamentally changed the economics of illicit distilling. Before 1920, moonshiners primarily competed with legal distilleries, keeping prices relatively low. With legal production eliminated, prices skyrocketed, and the profit margins on moonshine became enormous. A gallon of illegal whiskey that cost perhaps $2 to produce could sell for $20 or more in urban speakeasies. This financial incentive drew thousands of new producers into the trade and transformed what had been small family operations into more sophisticated enterprises. For those interested in exploring traditional recipes, try this pear moonshine mash recipe.

18th Amendment and the Rise of Bootlegging

The constitutional ban on alcohol created the perfect storm for moonshine’s golden age. While the law prohibited the production, transport, and sale of alcoholic beverages, it did nothing to eliminate demand. Americans didn’t suddenly lose their taste for spirits—they simply sought new, illegal sources. Moonshine producers, with generations of experience evading government oversight, were perfectly positioned to fill this void. For those interested in the craft, here’s a moonshine mash recipe with fruit that captures the essence of this storied tradition.

Prohibition created distinct roles in the illegal alcohol trade. “Moonshiners” made the product, while “bootleggers” handled transportation and distribution. This specialization allowed for greater efficiency and scale, as dedicated transporters could invest in modified vehicles specifically designed to outrun law enforcement. The network of relations between producers and distributors became increasingly sophisticated, with urban gangsters often providing financing for rural distilling operations in exchange for guaranteed supply.

The scale of moonshine production during Prohibition was staggering. By some estimates, more alcohol was consumed during Prohibition than before it, with much of that supply coming from illegal distilleries. Federal agents destroyed nearly 172,000 illegal stills between 1921 and 1925 alone, yet this represented only a fraction of the total operations. In areas like Franklin County, Virginia—nicknamed “The Moonshine Capital of the World”—illegal whiskey production became the dominant industry, employing thousands and generating millions in untaxed revenue.

Innovations in Still Design and Production

The tremendous demand during Prohibition drove significant innovations in still design and production techniques. Traditional copper pot stills, which produced relatively small batches, gave way to larger operations using more sophisticated equipment. “Submarine” stills—large, enclosed vessels capable of producing hundreds of gallons per run—became common in areas where distillers felt secure from law enforcement. Some operations grew so large that they required dedicated power sources and employed dozens of workers in various specialized roles.

While innovation improved efficiency, it sometimes came at the cost of quality and safety. The pressure to meet demand led some producers to cut corners, using substandard ingredients or rushing the distillation process. Sugar became a common substitute for grain in many operations, producing a faster but less flavorful spirit. More dangerously, some unscrupulous producers used radiators as condensers, introducing lead and other contaminants into their product, or failed to properly separate the toxic “foreshots” (containing methanol) from their runs. For a deeper understanding of these practices, you can explore the history of moonshine.

Famous Moonshiners and Their Legendary Runs

The Prohibition era elevated certain moonshiners to legendary status, creating folk heroes whose exploits were celebrated in song and story. Perhaps none is more famous than Marvin “Popcorn” Sutton, a Tennessee moonshiner who continued the tradition well into the 21st century. Sutton, with his long beard and colorful personality, became the archetype of the mountain moonshiner, eventually publishing his own guide to making moonshine and appearing in documentaries before his death in 2009. His legacy continues through legal brands that bear his name and recipes.

In Virginia, the name Willie Carter Sharpe struck fear in law enforcement and admiration among bootleggers. Known as the “Queen of the Bootleggers,” Sharpe transported moonshine from Franklin County to northern cities, making the treacherous journey hundreds of times. She was known for her custom-built cars with specialized compartments and her trademark diamond-studded teeth that would catch the moonlight as she sped past police roadblocks. By her own testimony, she delivered more than 800,000 gallons of moonshine and earned over $500,000 during her career.

Other notable figures include Alvin “Titanic” Thompson, who not only ran moonshine but became a legendary gambler, and Amos Owens, known as the “Cherry Bounce King” for his signature fruit-infused moonshine recipe. These individuals weren’t just criminals—they were entrepreneurs operating outside a legal system they viewed as unjust, often enjoying significant community support and protection. Their stories illustrate how moonshining was as much about cultural identity and economic independence as it was about alcohol production.

“They call me a bootlegger… I just make a little whiskey for my friends, and they never seem to have enough of it.” — Attributed to multiple famous moonshiners, including Popcorn Sutton

The Birth of NASCAR from Moonshine Drivers

Perhaps the most surprising cultural legacy of moonshining is its direct connection to the birth of NASCAR racing. The same drivers who delivered moonshine to thirsty customers developed extraordinary driving skills to evade law enforcement on winding mountain roads. These bootleggers modified ordinary cars with enhanced engines, heavy-duty suspension systems, and hidden compartments, creating vehicles that looked stock but performed far beyond factory specifications—the original “stock cars.”

Junior Johnson, who later became a NASCAR legend, got his start running moonshine through the hills of North Carolina. He developed the “bootlegger’s turn”—a 180-degree slide maneuver that allowed him to instantly reverse direction when confronted by police roadblocks. Similarly, stock car racing pioneer Red Vogt began as a mechanic specializing in preparing cars for moonshine runs before applying those same skills to early racing vehicles. These connections weren’t coincidental—when Bill France Sr. organized the first formal stock car races that would evolve into NASCAR, many of his early stars were current or former bootleggers.

Moonshine’s Technical Evolution

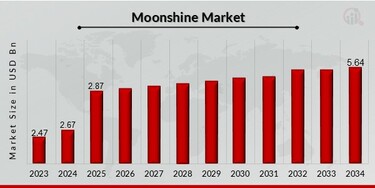

“Moonshine Market Size, Share, Report …” from www.marketresearchfuture.com and used with no modifications.

Behind the colorful stories and cultural impact of moonshine lies a sophisticated technical tradition that evolved over centuries. The equipment and techniques used to produce illicit spirits weren’t static but adapted continuously in response to changing conditions, available materials, and increased understanding of distillation science. This technical evolution reflects the ingenuity and resourcefulness that characterized the moonshining tradition.

From Pot Stills to Reflux Designs

The earliest American moonshiners used simple pot stills, directly descended from European designs. These basic apparatus consisted of a heated pot containing the fermented mash, connected to a condenser—typically a copper coil (the “worm”) immersed in cold running water. While inefficient by modern standards, these stills were relatively easy to construct from locally available materials and simple to operate. More importantly, they could be disassembled and relocated quickly when necessary, an essential feature for illicit operations.

As production demands increased, particularly during Prohibition, still designs grew more sophisticated. Reflux columns—which allow for multiple distillations in a single run—began to appear in larger operations. These taller columns contained plates or packing material that increased contact between rising vapor and condensing liquid, creating a more refined product with less fusel oil and impurities. The most advanced operations used hybrid systems that combined the best features of pot and column stills, allowing for both efficiency and flavor preservation.

Traditional Mash Bills and Recipes

The ingredients used in moonshine production varied widely by region and availability, though corn remained the foundation of most American recipes. A traditional corn liquor mash might contain 80-85% corn, with the remainder being a mix of malted barley (which provides necessary enzymes for starch conversion) and other grains like rye or wheat for flavor complexity. Sugar was often added to boost alcohol yield, particularly during Prohibition when production volume became paramount.

Regional variations created distinctive styles of moonshine. In Appalachia, a corn-dominant mash produced a sweet, distinct flavor profile. Louisiana moonshiners often used sugar cane as their primary fermentable, creating a product closer to rum. In fruit-growing regions, surplus apples, peaches, or berries were frequently added to the mash or used to infuse the finished spirit, creating distinctive seasonal products that reflected local agricultural patterns. For those interested in trying their hand at this, here’s a moonshine mash recipe with fruit to explore.

Dangerous Shortcuts: The Myth and Reality of Methanol Poisoning

The reputation of moonshine as dangerous or blinding stems largely from Prohibition-era shortcuts and adulterations rather than traditional production methods. Properly made moonshine—distilled from grain, with appropriate “cuts” separating the toxic foreshots (containing methanol) from the drinkable middle run—is no more dangerous than commercial spirits. Experienced moonshiners understood the importance of discarding the first portion of each run, which contains volatile compounds including methanol that distill at lower temperatures than ethanol.

The real dangers came from unscrupulous producers who either didn’t understand proper technique or deliberately cut corners. Some used car radiators as condensers, introducing lead into their product. Others added methanol (wood alcohol), formaldehyde, or other chemicals to increase potency or simulate the “burn” of higher-proof spirits. These adulterations, rather than moonshine itself, were responsible for the majority of poisoning cases that reinforced moonshine’s dangerous reputation.

- Proper distillation requires separating the “heads” (containing methanol and other volatile compounds)

- Lead poisoning often came from improvised equipment rather than the distillation process itself

- The “thump keg” used in traditional setups actually served as an additional purification step

- Traditional moonshiners tested their product by “proofing” with gunpowder or watching how bubbles behaved when the jar was shaken

Moonshine in American Culture

“It’s National Moonshine Day. We answer …” from www.cnn.com and used with no modifications.

Few indigenous American products have permeated our cultural consciousness like moonshine. From literature and film to music and television, white lightning has served as both cultural touchstone and dramatic device, often representing independence, rebellion, and rural ingenuity. This cultural representation has sometimes preserved authentic traditions while other times perpetuating harmful stereotypes about the people and regions associated with moonshine production.

Hillbilly Stereotypes in Media and Film

Hollywood’s portrayal of moonshiners has often leaned heavily on “hillbilly” stereotypes, depicting mountain distillers as comically unsophisticated or dangerously lawless. Films like “Thunder Road” (1958) starring Robert Mitchum captured some authentic elements of the bootlegging tradition while still exoticizing Appalachian culture. Later television programs like “The Dukes of Hazzard” further cemented the connection between moonshining and car chases in popular imagination, though with little attention to the actual craft of distilling.

More recent portrayals have attempted greater authenticity. Documentary series like “Moonshiners” on Discovery Channel have highlighted the technical skill and cultural traditions behind illicit distilling, though these too sometimes sensationalize or oversimplify a complex practice. The challenge for media representations has always been balancing entertainment value with respectful portrayal of communities that have often been marginalized in American society.

Music’s Connection to Mountain Whiskey

Music provides perhaps the most authentic cultural record of moonshining traditions. From traditional ballads like “White Lightning” and “Copper Kettle” to country classics like George Jones’s “White Lightning” and Steve Earle’s “Copperhead Road,” moonshine has inspired countless songs that capture both the danger and romance of illicit distilling. These musical accounts often preserve details of production methods, local terminology, and the social context of moonshining that might otherwise be lost to history.

The connection between moonshine and American music runs deeper than just lyrical content. Many early country and bluegrass performers came from communities where moonshining was common, and some, like legendary banjoist Grandpa Jones, had direct experience with the trade. The revenue from moonshining sometimes supported local musical traditions by providing disposable income for instruments and leisure time for practice in communities where economic opportunities were otherwise limited.

Oral Traditions and Family Stories

Despite its significance in American history, much of moonshine’s story remains undocumented in formal historical records. Instead, the traditions, techniques, and social contexts of moonshining have been preserved primarily through oral history—stories passed down through generations within families and communities where the practice was common. These narratives often contain detailed technical information about still construction, mash recipes, and fermentation techniques that constitute a valuable technical heritage.

Family moonshine stories typically emphasize themes of self-reliance, resourcefulness, and resistance to outside authority. They frequently highlight ingenious methods for evading law enforcement, from underwater stills operated by pulleys to elaborate signaling systems that warned of approaching revenue agents. While sometimes romanticized, these stories preserve important aspects of rural economic survival strategies and community solidarity that might otherwise be overlooked in conventional historical accounts. For those interested in the craft, exploring a moonshine mash recipe with fruit can offer a taste of this storied tradition.

The Legal Revolution: Craft Distilling Movement

“The future of craft distilling belongs …” from everglowspirits.com and used with no modifications.

The most significant development in moonshine’s long history may be its recent transition from outlawed substance to celebrated craft product. Beginning in the early 2000s, changes in federal and state licensing laws created opportunities for small-scale legal distilleries to produce and market unaged whiskey products explicitly connected to moonshining traditions. This legal revolution has brought techniques and recipes once shared only through whispered family traditions into the mainstream of American spirits production.

Changes in State Licensing Laws

The craft distilling renaissance began with crucial legal reforms that made small-scale commercial distilling economically viable for the first time since Prohibition. States like Oregon, Washington, and New York pioneered reduced licensing fees and created new categories of craft distillery permits that allowed for tasting rooms, direct sales to consumers, and self-distribution. These changes dramatically reduced the startup costs for legal distilleries and created viable business models for operations producing on a fraction of the scale of traditional commercial distilleries.

Federal excise tax reforms, particularly those included in the 2017 Craft Beverage Modernization and Tax Reform Act, further accelerated the trend by reducing the federal tax burden on small producers. The combined effect of these state and federal changes was explosive growth in the craft distilling sector, from fewer than 70 craft distilleries nationwide in 2003 to over 2,000 by 2020. Many of these new operations explicitly embraced moonshine heritage in their branding and product development.

How Prohibition-Era Recipes Influenced Modern Craft Spirits

The craft distilling movement didn’t just legalize moonshine production—it created a renaissance of interest in traditional recipes and methods. Many craft distillers actively sought out connections to historical moonshining traditions, sometimes recruiting former illicit distillers as consultants or researching family recipes that had been preserved through generations. This connection to authentic tradition became a powerful marketing advantage, allowing craft products to distinguish themselves from mass-produced commercial spirits.

The influence of moonshine traditions can be seen in both production techniques and product formulations. Many craft distillers have embraced direct-fire heating of pot stills, traditional grain bills with high corn content, and minimal filtration—all characteristics of traditional moonshine production. Some have even recreated historical equipment designs, including thumper kegs and worm condensers, though now built to modern safety standards and regulatory requirements.

First Wave of Legal “Moonshine” Brands

The pioneering legal moonshine brands emerged in the early 2000s, often in regions with strong historical connections to illicit distilling. Piedmont Distillers in North Carolina launched Midnight Moon in 2005, partnering with Junior Johnson to create a product explicitly linked to his family’s moonshining heritage. Ole Smoky Moonshine opened in Tennessee in 2010, becoming one of the first legal distilleries in a state with a rich but largely illicit distilling history. These early entrants established the commercial viability of unaged corn whiskey products that embraced rather than disguised their moonshine connections.

The success of these early brands triggered a wave of similar products, with varying degrees of authenticity. Some, like Howling Moonshine, were founded by individuals with direct family connections to the moonshining tradition, while others were created by entrepreneurs attracted to the marketing potential of moonshine’s outlaw mystique. This proliferation created both opportunities and challenges for consumers trying to distinguish products with genuine connections to historical traditions from those merely adopting the aesthetic.

What united these first-wave brands was their emphasis on transparency—both literally in their unaged, clear products, and figuratively in their production methods. Unlike traditional commercial distilleries that often obscured their industrial production processes, these new moonshine brands typically highlighted their methods, ingredients, and connections to regional traditions. This transparency helped educate consumers about distilling processes and created a market for authenticity that benefited producers committed to traditional methods. For those interested in exploring traditional recipes, check out this moonshine mash recipe with fruit.

| Era | Legal Status | Primary Production Areas | Typical Equipment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Colonial Period (1700s) | Legal until 1791 tax | Frontier settlements, Pennsylvania | Small copper pot stills |

| Post-Whiskey Rebellion (1800-1861) | Variable taxation | Appalachia, Kentucky, Tennessee | Pot stills with worm condensers |

| Civil War to Prohibition (1862-1919) | Illegal (untaxed) | Southern Appalachia primarily | Pot stills with thumper kegs |

| Prohibition (1920-1933) | Completely illegal | Nationwide, concentrated in rural areas | Larger submarine stills, some column stills |

| Post-Prohibition to 2000s | Illegal without permits | Isolated pockets in traditional regions | Mixed traditional and modern equipment |

| Craft Distilling Era (2000-present) | Legal with proper licensing | Nationwide craft distilleries | Modern equipment with traditional design elements |

Authentic vs. Commercial White Whiskey

As the legal moonshine category has grown, important distinctions have emerged between products that genuinely honor moonshine traditions and those that merely adopt the terminology for marketing purposes. Authentic moonshine-inspired products typically use corn-dominant mash bills, traditional distillation methods like pot stills or pot-column hybrids, minimal filtration, and little to no barrel aging. They often retain some of the grain oils and congeners that give moonshine its distinctive character and mouthfeel, rather than distilling to the neutral profile common in mass-produced white spirits.

By contrast, some commercial “moonshine” products are essentially neutral grain spirits with marketing that capitalizes on moonshine’s outlaw image. These products may be produced on industrial column stills designed to remove precisely the flavor compounds that give traditional moonshine its character. While not inherently inferior as spirits, these products have little connection to the technical tradition of American moonshining beyond their clear appearance and high proof. For consumers interested in authentic moonshine traditions, learning to distinguish between these approaches has become an important part of navigating the modern market.

Modern Craft Distilling: Honoring Moonshine Traditions

“Celebrating National Moonshine Day …” from www.liquorexam.com and used with no modifications.

Today’s craft distilling movement represents both a continuation and transformation of America’s moonshine heritage. The same spirit of independence and innovation that drove illicit distillers now powers a thriving legal industry that combines traditional techniques with modern scientific understanding. Rather than operating in hidden hollers under cover of darkness, contemporary craft distillers openly share their methods and stories, creating a new chapter in American spirits production that honors its outlaw roots while embracing technical advancement. For those interested in exploring different flavors, try making your own huckleberry moonshine at home.

The craft movement has democratized distilling knowledge that was once closely guarded. Books, classes, and online resources have made information about distillation techniques widely available, while legal changes have made small-scale commercial production viable. This openness has accelerated innovation and quality improvements while creating new appreciation for traditional methods that industrial production had largely abandoned. The result has been a renaissance in American distilling that draws directly from moonshine’s technical and cultural heritage.

For modern distillers, moonshine traditions offer not just historical curiosity but practical value. Many traditional techniques—from direct-fire heating to the use of local grains and minimal filtration—produce distinctive flavor profiles that set craft products apart from mass-produced alternatives. By studying and adapting these methods, contemporary distillers connect with centuries of practical knowledge while creating products suited to modern tastes and safety standards.

Unaged Whiskey’s Place in Today’s Market

Unaged corn whiskey, once dismissed by serious spirits enthusiasts, has found new appreciation in today’s diverse market. While aged whiskeys still dominate premium spirits categories, white whiskey offers unique transparency—both literally and figuratively. Without barrel aging to mask production flaws or homogenize flavor profiles, unaged spirits reveal the distiller’s skill and the quality of ingredients with nowhere to hide. This transparency has attracted consumers interested in understanding the fundamental character of spirits before wood influence is added.

Traditional Techniques in Commercial Production

Many craft distillers have found ways to incorporate traditional moonshine techniques into commercial production while meeting modern regulatory and safety requirements. Open-flame heating, once used by necessity in hidden operations, has been reintroduced in some craft distilleries for the distinctive flavor profile it creates. Similarly, thumper kegs—secondary chambers that perform a kind of additional distillation in traditional setups—have been adapted to meet modern safety standards while preserving their flavor-enhancing functions.

The emphasis on local ingredients that characterized traditional moonshine has also found new expression in the craft movement. Many distilleries source corn and other grains from local farmers, sometimes even specifying heritage varieties with distinctive flavor profiles. This connection to local agriculture mirrors the practice of early moonshiners, who typically used whatever grains they grew themselves or could source locally, creating regional flavor profiles that reflected local agricultural conditions.

The Rise of Flavored Moonshine Products

Perhaps the most visible modern adaptation of moonshine traditions has been the explosion of flavored products. While traditionalists sometimes criticize these products as departures from authentic moonshine, they actually have deep historical roots. Mountain distillers frequently infused their spirits with local fruits, herbs, or honey—creating products like apple pie moonshine, cherry bounce, or honey moonshine that served both as flavorful beverages and folk medicines. Modern flavored moonshines, when made with real ingredients rather than artificial flavorings, represent a continuation rather than abandonment of these traditions.

The Future Shines Bright: Moonshine’s Ongoing Legacy

“New Drop Zone Distillery bringing …” from www.youtube.com and used with no modifications.

The story of American moonshine continues to evolve as new generations discover and reinterpret this distinctive national tradition. After surviving centuries of prohibition, prosecution, and cultural stigmatization, moonshine has emerged into the light as a celebrated part of American heritage. Today’s craft distillers don’t just preserve moonshine traditions—they actively develop them, creating innovative products that honor their historical roots while meeting contemporary expectations for quality, consistency, and safety. For those interested in exploring the diverse flavors of moonshine, experimenting with a blueberry moonshine recipe can be a delightful way to experience this ongoing legacy.

As interest in authentic local traditions continues to grow, moonshine’s future seems secure. The same independent spirit that drove generations of illicit distillers now fuels a thriving craft industry that connects consumers to distinctive regional flavors and production methods. Whether enjoyed in a traditional mason jar or a sophisticated cocktail glass, modern moonshine offers a taste of American history and a connection to the resourceful spirit that has defined our national character. As regulations continue to evolve and craft distilling knowledge spreads, we can expect further innovations that build upon this foundation while respecting the traditions that made it possible.

Frequently Asked Questions

Moonshine’s complex history and technical nature naturally generate many questions from those new to the tradition. Below are answers to some of the most common inquiries about America’s native spirit, addressing both historical aspects and modern considerations for enthusiasts.

Is moonshine illegal to make at home today?

Yes, producing distilled spirits at home without proper federal permits remains illegal throughout the United States, regardless of quantity or whether it’s for personal use. While home brewing of beer and wine became legal federally in 1978, home distillation remains prohibited under federal law. The penalties can be severe, including up to 5 years imprisonment and $10,000 in fines for first-time offenders. This prohibition stems from both taxation concerns and safety considerations around the flammable nature of distillation and potential methanol hazards.

What makes real moonshine different from commercial white whiskey?

Authentic moonshine typically has a more robust flavor profile than many commercial white whiskeys, particularly those produced on industrial column stills. Traditional moonshine retains more of the grain oils and congeners that give it a distinctive corn-forward character and sometimes a slight oiliness on the palate. The production method also matters—moonshine made in pot stills or with thumper kegs often has more complexity than spirits from continuous stills.

Another key difference lies in filtration approaches. Commercial white whiskeys are often heavily filtered to remove color and certain flavor compounds, creating a cleaner but sometimes less distinctive product. Traditional moonshine typically undergoes minimal filtration, preserving more of the grain character and sometimes resulting in a slight haze, especially when chilled. These differences aren’t necessarily indicators of quality—they represent different production philosophies and intended flavor profiles.

Why was moonshine historically so dangerous to drink?

Properly produced moonshine made by experienced distillers was generally no more dangerous than commercial spirits. The dangers associated with historical moonshine stemmed primarily from poor production practices rather than moonshine itself. The most serious risks came from improper separation of methanol (which distills at a lower temperature than ethanol) in the early part of the distillation run. Experienced moonshiners knew to discard this portion (called the “foreshots”), but unscrupulous or unskilled producers sometimes included it to increase volume.

Additional dangers came from improper equipment, particularly during Prohibition when demand outstripped the supply of proper copper stills. Some producers used car radiators as condensers, which could introduce lead and other toxic metals into the final product. Others deliberately adulterated their spirits with methanol, formaldehyde, or other chemicals to increase potency or simulate the “burn” of higher-proof alcohol.

- Methanol poisoning caused blindness and death in extreme cases

- Lead poisoning from improper equipment created chronic health problems

- Sugar-based recipes fermented in unsanitary conditions could develop bacterial contamination

- Excessively high proof without proper dilution created fire hazards and increased alcohol poisoning risks

Modern legal “moonshine” eliminates these risks through regulatory oversight, proper equipment, and scientific testing of each batch before release. Today’s craft distillers combine traditional techniques with modern understanding of safe distillation practices, creating products that honor the heritage of moonshine without the historical hazards.

Did moonshiners really outrun the law in souped-up cars?

Absolutely—the connection between moonshine running and high-performance driving is one of the most authentic aspects of moonshine lore. During Prohibition and the decades that followed, bootleggers modified ordinary-looking cars with powerful engines, enhanced suspension systems, and reinforced frames to transport their illicit cargo while outrunning law enforcement. These vehicles needed to be fast enough to escape pursuit but inconspicuous enough not to attract attention before being spotted.

The technical innovations developed by moonshine runners directly influenced early stock car racing and ultimately contributed to the formation of NASCAR. Legendary drivers like Junior Johnson, who won 50 NASCAR races, got their start running moonshine on winding mountain roads. The driving techniques they developed—like power sliding through turns and the “bootlegger’s reverse”—became foundational skills in early stock car racing. Even the term “stock car” itself reflects this heritage, as the original concept was to race cars that appeared stock on the outside while concealing significant performance modifications—exactly like the vehicles used to transport moonshine.

What’s the proper way to drink traditional moonshine?

Traditionally, moonshine was most often consumed straight and at room temperature, often passed around in mason jars at social gatherings. The unaged spirit wasn’t meant for sophisticated sipping like aged whiskeys—it was typically consumed in small amounts, valued as much for its potency as its flavor. In mountain communities, moonshine was sometimes mixed with honey, herbs, or fruits, both for flavor and for perceived medicinal benefits. These traditions gave rise to favorites like apple pie moonshine, where the spirit was infused with apple cider, cinnamon, and sugar.

Modern craft distillers have expanded the ways to enjoy unaged corn whiskey. While it can certainly be enjoyed neat to appreciate its raw character, today’s moonshine also works well in cocktails that highlight rather than mask its distinctive grain-forward profile. The simplest approach is to substitute moonshine for vodka or white rum in familiar recipes—a moonshine mule (with ginger beer and lime) or moonshine sour (with lemon juice and simple syrup) can showcase the spirit’s character while tempering its intensity.

For the most authentic experience, some enthusiasts prefer to chill moonshine in the freezer before drinking—a practice that dates back to illicit production days when higher proof made the spirit resistant to freezing. This approach mutes some of the alcohol heat while emphasizing the corn sweetness. Whatever your preference, the key is to respect the spirit’s heritage while finding ways to appreciate its distinctive character in a modern context. At Howling Moonshine, we honor these traditions while creating products that meet contemporary expectations for quality and consistency. To delve deeper into moonshine’s storied past, check out the history of moonshine.