Moonshine in Appalachia: How a Rural Tradition Shaped American Distilling

Article-at-a-Glance

- Appalachian moonshine originated from Scots-Irish immigrants who brought their whiskey-making traditions to America’s isolated mountain regions, creating a resilient economic solution for impoverished farmers.

- The craft of illicit distilling flourished during Prohibition, creating a distinctive “cat-and-mouse” culture between moonshiners and federal revenue agents that shaped American folklore.

- Traditional distilling methods using copper stills, pure mountain water, and corn mash created a distinctive spirit that influenced modern craft distilling techniques.

- Legendary moonshiners like Popcorn Sutton preserved centuries-old recipes and techniques that are now being revived by legitimate craft distilleries across the Appalachian region.

- From its outlaw origins to mainstream acceptance, Appalachian moonshine represents one of America’s most authentic contributions to global spirits culture.

Deep in the misty hollows of Appalachia, a spirit was born that would forever change American drinking culture. Not just a high-proof alcohol, but a symbol of independence, ingenuity, and resistance against outside control. The story of moonshine isn’t just about making liquor—it’s about survival, tradition, and the indomitable spirit of mountain people who transformed necessity into craft.

While many see moonshine as merely an illicit backwoods drink, its importance to American distilling cannot be overstated. From the earliest settlement days through Prohibition and into modern craft distilling, the techniques and traditions of Appalachian moonshiners have shaped how America produces and consumes spirits. Today, those once-secretive methods are celebrated in premium craft distilleries across the country, many founded by passionate artisans dedicated to preserving authentic mountain traditions while bringing them to new audiences.

The mountains themselves were essential characters in this story, providing both the necessary isolation and the perfect natural resources for spirit-making. What began as economic necessity evolved into a proud cultural tradition passed through generations, surviving despite relentless persecution and changing times.

The Birth of Appalachian Moonshine: Necessity Born From Hardship

“Paw Paw moonshine flows at Appalachian …” from brilliantstream.com and used with no modifications.

Scots-Irish Roots and Mountain Isolation

The story of Appalachian moonshine begins across the Atlantic, where distilling traditions had deep roots in Scottish and Irish culture. When waves of Scots-Irish immigrants arrived in America during the 18th century, they brought their whiskey-making knowledge with them. These settlers were drawn to the Appalachian mountains not just for available land but for something equally valuable to distillers: privacy. The region’s isolated hollows, dense forests, and rugged terrain created natural barriers that kept government officials and tax collectors at bay.

This geographic isolation proved crucial for the development of America’s moonshine tradition. Far from markets and major transportation routes, Appalachian settlers created self-sufficient communities where traditional practices could be maintained without outside interference. Water sources were abundant, with countless springs and streams providing the pure, mineral-rich water essential for quality spirits. The mountains themselves offered natural hiding places for stills and storage, with caves, dense forest cover, and remote hollows providing security from unwanted visitors.

“In them hills, a man could breathe free. Government men didn’t much like climbin’ them steep slopes just to see what you might be cookin’ up. That’s how we kept our ways, same as our granddaddies before us.” – Anonymous Appalachian distiller, 1952

Corn to Liquor: The Perfect Economic Solution

Moonshining wasn’t born from a desire to break laws—it emerged as a practical economic solution for mountain farmers facing nearly impossible circumstances. In the isolated hollows of Appalachia, farmers could grow corn in abundance, but transporting heavy grain to distant markets over mountain trails was impractical and unprofitable. Converting corn into whiskey solved multiple problems simultaneously: it preserved the crop value, reduced transportation bulk dramatically, and created a high-value product that could be sold or bartered.

The math was compelling for struggling mountain families. A bushel of corn worth less than a dollar could be transformed into several gallons of whiskey worth many times more. This conversion wasn’t just profitable—it was essential for survival in an economy where cash was scarce and opportunities limited. What began as economic necessity soon developed into a cultural tradition and source of regional pride.

When Alexander Hamilton pushed through the first federal excise tax on distilled spirits in 1791, he unwittingly created the conditions that would define moonshining for centuries. For Appalachian farmers, the tax wasn’t simply an inconvenience—it threatened their primary means of economic survival. Refusing to pay what they viewed as an unjust tax, mountain distillers moved their operations deeper into the hollows, developing the secretive practices that would become synonymous with moonshine production.

White Lightning: The Craftsmanship Behind Illicit Spirits

“YULE 4oz. Alchemy RITUAL SMUDGE SPRAY …” from www.whitewitchparlour.com and used with no modifications.

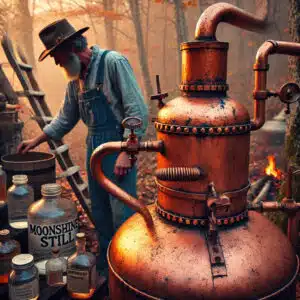

Traditional Distilling Methods in the Hollows

Behind the outlaw reputation of moonshine lies a tradition of remarkable craftsmanship. Contrary to popular misconceptions about crude production methods, traditional Appalachian moonshiners developed sophisticated techniques that produced exceptional spirits. The distillation process followed meticulous steps refined over generations, with family recipes guarded as precious heirlooms. Quality moonshine required not just equipment but extensive knowledge and skills passed from distiller to apprentice through direct instruction and observation.

The process typically began with a “mash” of ground corn, malted barley, water, and sometimes sugar, allowed to ferment in wooden barrels. Temperature control was critical during fermentation, with experienced moonshiners using their senses rather than instruments to judge when conditions were right. After fermentation, the liquid was carefully transferred to the still, where the actual distillation would occur. This process required constant attention and adjustment, with the distiller making crucial decisions based on appearance, smell, and even the sound of the boiling mash.

The Secret Recipe: Corn, Water, and Appalachian Ingenuity

While the basic ingredients of moonshine were simple—primarily corn, water, and yeast—the variations in recipes created distinctive regional styles across Appalachia. Some distillers added sugar to increase alcohol content, while others insisted on pure grain mash for superior flavor. Many incorporated small amounts of rye, wheat, or barley to add complexity. The proportions and preparation methods became closely guarded secrets, with subtle differences distinguishing one family’s product from another’s.

Copper Stills and Mountain Streams

At the heart of traditional moonshine production stood the copper still—a piece of equipment that represented both technical ingenuity and cultural heritage. Copper wasn’t chosen by accident; it serves critical functions in the distillation process, removing sulfur compounds and imparting distinctive flavors impossible to achieve with other materials. Master craftsmen constructed these stills by hand, carefully hammering sheets of copper into the required shapes, soldering joints with precision, and creating condensation coils that efficiently converted vapor back to liquid.

The location of these operations was selected with strategic care. Proximity to clean, cold mountain water sources was essential—not just for the whiskey itself, but for cooling the condensation coils during distillation. Moonshiners became expert hydrologists, identifying springs with ideal mineral compositions and constructing elaborate water-diversion systems to feed their operations. The most successful operations maintained multiple still sites, rotating between them to avoid detection while ensuring continuous production.

These mountain streams contributed more than convenience; they provided distinctive flavor profiles that varied from hollow to hollow. Some regions became known for particularly smooth or flavorful moonshine based partly on their unique water sources—creating what we would now recognize as “terroir” in spirit production, long before such concepts became fashionable in commercial distilling.

Running From Revenue: The Cat-and-Mouse Game

.jpg)

“Stop Chasing Revenue: Why Cash Flow Is …” from www.certaintynews.com and used with no modifications.

The Whiskey Rebellion and Federal Taxes

The confrontation between mountain distillers and government authorities began almost immediately after the founding of the United States. When the newly formed federal government imposed its first excise tax on spirits in 1791, the response was swift and violent. Western Pennsylvania erupted in what became known as the Whiskey Rebellion, with farmers and distillers actively resisting tax collection. Though President Washington ultimately suppressed this organized resistance with military force, the spirit of defiance merely retreated deeper into the mountains.

In Appalachia, resistance to alcohol taxation wasn’t simply about money—it represented a fundamental conflict between mountain independence and external authority. For families who had fled oppressive conditions in Europe or sought freedom on the frontier, government taxation of homemade spirits symbolized exactly the kind of interference they had sought to escape. This resistance created a lasting cultural legacy where producing untaxed whiskey became not merely an economic activity but a political statement about freedom and self-determination.

Through the 19th century, federal efforts to collect spirits taxes waxed and waned with changing political priorities. During the Civil War, desperate for revenue, the Union government dramatically increased alcohol taxation and enforcement, permanently establishing the foundation for the modern conflict between moonshiners and revenue officers. This pattern—government financial needs driving increased enforcement, followed by more sophisticated evasion techniques—would repeat throughout American history.

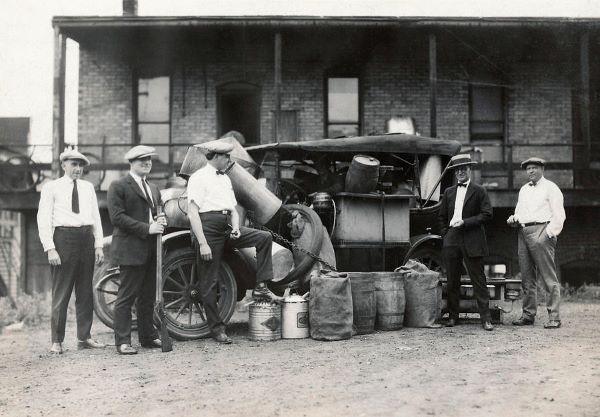

Prohibition’s Golden Era for Moonshiners

If any single event transformed moonshining from local tradition to national phenomenon, it was Prohibition. When the Eighteenth Amendment banned the production and sale of alcoholic beverages in 1920, it created unprecedented demand for illicit spirits. Suddenly, skills developed over generations in mountain hollows became extraordinarily valuable across America. Appalachian moonshiners scaled up production dramatically, creating distribution networks reaching major cities hundreds of miles from their stills.

The Prohibition era (1920-1933) represented both opportunity and danger for mountain distillers. Prices for moonshine skyrocketed, creating wealth for some producers who had previously lived in poverty. However, increased profits attracted both organized crime and intensified federal enforcement. The Bureau of Prohibition deployed hundreds of agents specifically targeting moonshine operations, resulting in frequent raids, shootouts, and imprisonments throughout Appalachia.

Even after Prohibition’s repeal in 1933, high taxes on legal alcohol ensured continued demand for untaxed spirits. Mountain moonshiners adapted to changing circumstances, developing more sophisticated methods of production, concealment, and distribution that would sustain the tradition through much of the 20th century. These innovations included hidden trap doors, false walls, underground storage facilities, and elaborate warning systems to alert distillers when revenue agents approached.

Federal Revenue Agents vs. Mountain Distillers

The conflict between moonshiners and federal revenue agents evolved into a decades-long game of tactical innovation and counter-innovation. Revenue agents employed increasingly sophisticated techniques—aerial surveillance, informant networks, and infiltration operations—while moonshiners responded with hidden stills, lookout systems, and elaborate escape routes. The dangers were real for both sides; numerous revenue agents and moonshiners died in armed confrontations that sometimes escalated into extended gun battles.

The cat-and-mouse game created its own folklore and heroes on both sides. Legendary revenue agents like Mike Thompson became known for their uncanny ability to locate hidden operations, while master moonshiners achieved folk hero status for their daring escapes and clever deceptions. Stories of narrow escapes, betrayal, and creative still designs became central to Appalachian oral tradition, often embellished with each retelling. These narratives reinforced a regional identity where cunning and self-reliance were celebrated as essential virtues.

By the mid-20th century, the federal government had dramatically increased resources devoted to suppressing illegal distilling. The Alcohol Tax Unit (later the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives) conducted thousands of raids annually throughout Appalachia, destroying stills and arresting producers. Despite these intensified efforts, the practice persisted in the most remote mountain communities where alternative economic opportunities remained scarce and cultural traditions strong. Some enthusiasts even explored ways on how to make moonshine taste smooth to enhance their craft.

NASCAR’s Secret Origins in Moonshine Running

One of the most fascinating legacies of the moonshine tradition emerged on the winding mountain roads of Appalachia—the birth of stock car racing. Delivering illegal whiskey required vehicles that could outrun law enforcement while carrying heavy loads over treacherous mountain roads. Moonshine runners modified ordinary-looking cars with powerful engines, enhanced suspension systems, and hidden compartments, developing driving skills that would eventually transform American motorsports.

These moonshine runners—among them legendary figures like Junior Johnson, who later became NASCAR royalty—gathered on weekends to race their delivery vehicles for bragging rights and entertainment. These informal competitions gradually evolved into organized events that attracted growing audiences. When Bill France Sr. organized these races into the National Association for Stock Car Auto Racing (NASCAR) in 1947, he built upon foundations laid by generations of whiskey runners who had perfected both car modification techniques and driving skills evading federal agents.

The connection between moonshining and early NASCAR wasn’t merely coincidental—many of the sport’s pioneering drivers and mechanics came directly from the moonshine trade, bringing with them specialized knowledge about engine performance, weight distribution, and handling at high speeds. This heritage is acknowledged today as an essential part of NASCAR’s origin story, representing one of the most visible ways that Appalachian moonshine culture influenced mainstream American life.

From Outlaws to Icons: Legendary Moonshiners of the Mountains

“Popcorn Sutton – Wikipedia” from en.wikipedia.org and used with no modifications.

Throughout Appalachian history, certain moonshiners transcended their outlaw status to become cultural icons whose influence extended far beyond their mountain communities. These individuals weren’t merely producers of illicit spirits—they were keepers of tradition, master craftsmen, and symbols of resistance against outside control. Their stories, passed through generations, helped transform moonshining from criminal activity to cultural heritage worthy of preservation and respect.

Popcorn Sutton and His Lasting Legacy

No figure better exemplifies the transition of moonshiner from outlaw to icon than Marvin “Popcorn” Sutton. Born in Maggie Valley, North Carolina in 1946, Sutton learned distilling from his father and grandfather, becoming a living link to centuries of tradition. With his distinctive appearance—long beard, battered hat, and overalls—and unfiltered personality, Sutton embodied the independent mountain spirit for a new generation. What distinguished him from countless anonymous distillers was his willingness to document and share his knowledge, famously producing a home video called “This is the Last Dam Run of Likker I’ll Ever Make” that detailed his production methods.

Sutton’s legend grew when he published his autobiographical guide “Me and My Likker” in 1999, providing unprecedented documentation of traditional moonshining techniques. Though he continued to have run-ins with the law, facing significant prison time in his final years, Sutton’s contribution to preserving authentic moonshine traditions proved invaluable. His 2009 suicide, reportedly to avoid federal prison, transformed him into a martyr figure for mountain independence. Perhaps most ironically, his recipes and methods now form the foundation for Popcorn Sutton’s Tennessee White Whiskey—a legally produced commercial spirit based directly on his once-illegal techniques.

“I’m a mountain man, and I want to do my own stuff. I’ve been making whiskey all my life, and I want to keep on doing it. Jesus turned water into wine, and I turned corn into whiskey. It’s all the same thing.” – Popcorn Sutton

Family Traditions Passed Through Generations

Beyond famous figures like Sutton, the true heart of Appalachian moonshine culture resided in hundreds of families who preserved distilling knowledge across generations. Moonshine production was rarely a solitary pursuit; it typically involved multiple family members working together in roles developed through years of practice. Children might begin by gathering firewood or keeping watch for strangers before gradually learning more complex aspects of the process. By adolescence, many had absorbed comprehensive knowledge about mash preparation, fermentation monitoring, and still operation.

These family traditions created distinctive regional styles, with subtle variations in technique and recipe producing recognizable differences in flavor, potency, and character. In some communities, certain families became known for particular specialties—one might produce the smoothest drinking whiskey, while another excelled at high-proof “white lightning” valued for its potency. These reputations were fiercely protected and enhanced through generations, creating a form of brand identity long before commercial marketing concepts existed.

The transmission of knowledge typically occurred through direct demonstration rather than written instructions. Apprentice distillers learned by watching, assisting, and gradually taking on more responsibility under the guidance of experienced family members. This oral tradition ensured that techniques remained adaptive—each generation could incorporate improvements while maintaining core methods that had proven successful over time. Even as economic opportunities drew younger generations away from mountain communities, many families maintained their distilling knowledge as a connection to their heritage.

Modern Revival: Appalachian Moonshine Goes Legitimate

“Bootleg moonshine, ‘likker’ go legit” from www.amarillo.com and used with no modifications.

The Legalization Journey

The transformation of moonshine from illicit backwoods liquor to legitimate craft spirit represents one of the most remarkable evolutions in American distilling history. This journey began in earnest during the early 2000s when changing regulatory environments and growing consumer interest in authentic regional products created opportunities for traditional moonshiners to “go legal.” States across Appalachia began modifying laws to accommodate small-scale distilleries, reducing licensing fees and simplifying the regulatory process that had previously made legal operation prohibitively expensive.

Tennessee’s 2009 legislation proved particularly significant, expanding legal distilling beyond Moore, Coffee, and Lincoln counties for the first time since Prohibition. Within months, distilleries began appearing in previously dry counties throughout eastern Tennessee’s mountain communities. North Carolina, Virginia, Kentucky, and other Appalachian states soon followed with their own reforms, creating a regulatory framework that allowed traditional methods to emerge from the shadows while ensuring consumer safety and tax compliance.

For many former illegal distillers, the transition to legitimate business presented both opportunities and challenges. The skills developed through generations of clandestine production translated well to commercial operations, but adapting to regulatory requirements, marketing demands, and business management required significant adjustment. Those who successfully navigated this transition often discovered that their authentic connection to moonshine heritage provided powerful marketing advantages in an increasingly crowded craft spirits marketplace.

Craft Distilleries Honoring Mountain Traditions

Today, dozens of legitimate distilleries across Appalachia proudly trace their methods directly to moonshining traditions. These operations range from small family businesses producing a few hundred gallons annually to larger enterprises distributing products nationwide. What unites them is their commitment to authentic production methods—using copper stills, local ingredients, and techniques developed through centuries of mountain distilling. Many employ former moonshiners as master distillers or consultants, ensuring that traditional knowledge continues to inform commercial production. For those interested in the intricacies of the craft, understanding how to make moonshine taste smooth is a key aspect of preserving these time-honored techniques.

Distilleries like Ole Smoky in Tennessee, Copper Fox in Virginia, and Call Family Distillers in North Carolina have built successful businesses explicitly connecting their products to moonshine heritage. They often occupy a fascinating middle ground—fully compliant with modern regulations while celebrating their connections to once-illegal practices. Their marketing materials frequently feature stories of moonshining ancestors, historic photographs of mountain stills, and references to regional distilling traditions that survived despite decades of prohibition and persecution.

This authenticity resonates strongly with consumers seeking connections to American heritage and traditional craftsmanship. While mass-market spirits emphasize consistency and brand identity, these Appalachian distilleries celebrate the distinctive characteristics that emerge from traditional methods—batch variations, local grain influences, and production techniques that industrial processes cannot replicate. For many consumers, these connections to authentic mountain traditions represent the primary appeal of modern moonshine products.

Tourism and Cultural Heritage Preservation

The legalization of traditional distilling has created significant economic opportunities beyond spirit production itself. Moonshine heritage has become a powerful driver of tourism throughout Appalachia, with distillery tours, museums, and themed attractions drawing visitors from across America and internationally. The Tennessee Whiskey Trail, Kentucky Bourbon Trail, and similar routes now include stops at distilleries explicitly celebrating their moonshine connections, creating tourism corridors through communities that previously saw few outside visitors. For those interested in the distillation process, exploring the best yeast for moonshine can enhance the experience.

This tourism boom has supported broader cultural heritage preservation efforts throughout the region. Museums like the Appalachian Heritage Museum in Kentucky and the Mountain Gateway Museum in North Carolina maintain extensive exhibits documenting moonshine history, displaying historic equipment and photographs while recording oral histories from elderly community members with firsthand knowledge of traditional practices. These preservation efforts ensure that the cultural significance of moonshining—beyond simply producing alcohol—remains accessible to future generations.

Perhaps most significantly, the legitimization of moonshine has allowed Appalachian communities to reclaim this aspect of their heritage with pride rather than secrecy or shame. What was once discussed in whispers or denied entirely is now celebrated openly as a distinctive cultural tradition demonstrating mountain ingenuity, craftsmanship, and resistance. This cultural rehabilitation has particular significance for communities that have frequently seen their traditions misrepresented or dismissed by outside observers.

Moonshine’s Influence on American Distilling Practices

“Copper Moonshine Stills” from acestills.com and used with no modifications.

Craft Spirit Revolution’s Appalachian Roots

The broader American craft distilling movement, which has exploded over the past two decades, owes significant debts to Appalachian moonshine traditions. While craft brewing established the consumer market for locally-produced, small-batch alcoholic beverages, it was the moonshine heritage that provided crucial production knowledge for early craft distillers. Many pioneering craft operations across the country either consulted with former moonshiners or studied traditional methods when establishing their production processes.

This influence extends beyond white whiskey to the entire craft spirits industry. Techniques for small-batch fermentation, direct-fire distillation, and flavor development through careful cuts—all central to moonshine production—have become standard practices in craft distilleries producing everything from bourbon to gin. The emphasis on local ingredients and regional flavor profiles, long essential to moonshine tradition, has similarly become a defining characteristic of the craft spirits movement nationwide.

Perhaps most importantly, moonshine heritage provided a compelling narrative of American authenticity that helped distinguish craft products from industrial spirits. Stories of mountain stills, federal agents, and recipes passed through generations created marketing advantages that early craft distillers leveraged effectively. These narratives resonated particularly strongly with consumers seeking connections to traditional American craftsmanship and independence—values embodied by the moonshining tradition.

Traditional Methods in Modern Premium Spirits

The technical influence of moonshine traditions on modern distilling extends far beyond white unaged whiskey. Techniques developed through generations of illicit production—particularly those involving small-scale batch management, hands-on quality assessment, and precise control of distillation cuts—have been embraced by premium producers across all spirit categories. The moonshiner’s reliance on sensory evaluation rather than automated controls has particularly influenced the artisanal approach now prevalent in high-end spirit production, where master distillers make critical decisions based on sight, smell, and taste rather than purely technical measurements.

From Mason Jars to Marketing: How Moonshine Entered the Mainstream

“THE HISTORY OF MOONSHINE | Backroads …” from backroadsliquorhouse.com and used with no modifications.

The journey of moonshine from hidden hollows to retail shelves represents one of the most remarkable transformations in American spirits history. What was once defined by its illegality and underground distribution has become a legitimate commercial category with dedicated shelf space in liquor stores nationwide. This transition required both regulatory changes and significant cultural shifts that transformed public perception of white whiskey from dangerous contraband to heritage product worth premium prices.

Early commercial moonshine faced significant marketing challenges. Producers needed to maintain authentic connections to mountain heritage while distancing themselves from negative associations with methanol poisoning, criminal networks, and unsafe production methods. The solution emerged through careful brand storytelling that emphasized craftsmanship, family tradition, and regional identity while highlighting modern safety standards and regulatory compliance. Clear glass jars resembling traditional mason jars became the industry’s signature packaging, visually connecting commercial products to their historical roots.

The commercial category expanded dramatically between 2010 and 2020, with major beverage corporations acquiring pioneering brands while introducing their own white whiskey products. This mainstreaming brought both opportunities and challenges for traditional producers, who found themselves competing against marketing budgets and distribution networks far exceeding their own resources. Those who survived this competition typically did so by doubling down on authentic heritage connections that mass-market competitors couldn’t credibly claim.

- Traditional mason jar packaging adapted for retail sales

- Development of flavor-infused varieties (apple pie, blackberry, peach) based on traditional home recipes

- Premium pricing strategies positioning moonshine as craft product rather than budget alternative

- Tasting room experiences emphasizing education about production methods and historical context

- Cross-marketing with regional tourism, creating “moonshine trails” through Appalachian communities

Television, Music, and Pop Culture References

Moonshine’s cultural rehabilitation received enormous boosts from television programs, music, and other media that transformed public perception of mountain distilling. Shows like Discovery Channel’s “Moonshiners” brought traditional production methods into millions of homes, portraying practitioners as skilled craftspeople maintaining valuable traditions rather than simply criminals evading taxes. While these programs sometimes exaggerated dangers and conflicts for dramatic effect, they nevertheless introduced authentic production techniques to audiences who would never visit an Appalachian still site. Similarly, reality competitions like “Master Distiller” showcased the technical skill and creativity involved in traditional whiskey production.

Flavored Varieties and Commercial Success

One of the most significant innovations in commercial moonshine has been the development of flavored varieties based on traditional “kitchen table” recipes. While purists might insist that true moonshine is clear corn whiskey, many mountain families historically created flavored versions for home consumption—particularly fruit-infused varieties that masked harsh edges while making the product more appealing to casual drinkers. Commercial distilleries have expanded on these traditions, creating apple pie, blackberry, peach, and countless other flavored products that now dominate the category’s sales. These sweeter, more accessible products have brought moonshine to consumers who would never consider drinking traditional white whiskey, dramatically expanding the market while creating entirely new product categories.

The Spirit of Appalachia Lives On

“Appalachia and the spirit in the …” from wildhunt.org and used with no modifications.

The transformation of moonshine from outlawed necessity to celebrated heritage represents more than just a change in legal status—it embodies the resilience of Appalachian culture and its growing influence on American craft production. What began as economic adaptation by isolated mountain communities has evolved into a nationwide appreciation for traditional methods, authentic ingredients, and the distinctive character that emerges from small-batch production. While commercial success has inevitably changed aspects of the tradition, the core values remain: independence, resourcefulness, craftsmanship, and connection to place. As new generations discover these traditions through legitimate distilleries, the spirit of Appalachian moonshine continues to evolve while maintaining its essential character, ensuring that knowledge developed through centuries of mountain distilling will inform American spirits production for generations to come.

Frequently Asked Questions

The mystique surrounding moonshine has generated persistent questions about its production, legality, and characteristics. While some common beliefs about mountain whiskey contain elements of truth, others represent misconceptions perpetuated through popular culture. Understanding the reality behind the legends provides deeper appreciation for this distinctive American tradition.

Beyond basic questions about production and legality, many enthusiasts seek information about experiencing authentic moonshine within today’s regulatory environment. The good news is that legitimate options now exist for those wanting to taste traditional Appalachian spirits without risking legal consequences or safety concerns. For those interested in understanding more about these moonshining traditions, there are resources available that delve into the history and cultural significance of this craft.

These frequently asked questions address the most common inquiries about moonshine tradition, helping separate fact from fiction while providing practical guidance for those interested in exploring this aspect of American heritage.

What exactly makes a spirit “moonshine” versus other whiskeys?

Technically speaking, moonshine refers to any spirit produced without government oversight or taxation, regardless of ingredients or production methods. However, in Appalachian tradition, authentic moonshine is typically an unaged corn whiskey produced in a pot still. Unlike commercial bourbon or other whiskeys that gain color and flavor from barrel aging, traditional moonshine goes directly from still to container, resulting in a clear spirit. The corn base (usually 80-85% of the grain bill) provides distinctive sweetness, while the unaged character allows the distillation quality and grain flavors to come through without the mellowing influence of oak. Today’s commercial “moonshine” products maintain these characteristics—clear, corn-based, unaged—while complying with regulatory requirements that their illegal predecessors avoided.

Is homemade moonshine still illegal today?

Yes, producing distilled spirits without appropriate federal and state permits remains illegal throughout the United States. Federal law prohibits the distillation of spirits for personal consumption (unlike homebrewing beer or making wine, which are legal in limited quantities), and penalties can include significant fines and imprisonment. The prohibition applies regardless of quantity or whether the spirits are for personal use or sale. This legal status reflects both taxation concerns and safety considerations—improperly produced spirits can contain dangerous compounds like methanol. Those interested in moonshine heritage can legally experience it by purchasing from licensed distilleries or attending supervised educational demonstrations at museums and heritage sites where special permits have been obtained.

What gives authentic moonshine its distinctive taste?

Traditional moonshine’s flavor profile comes from several key factors: the predominance of corn in the grain bill, the use of copper stills, direct-fire heating methods, and careful attention to “cuts” during distillation. The corn base provides natural sweetness, while proper distillation in copper removes sulfur compounds that would create off-flavors. Master moonshiners are particularly skilled at making precise “cuts”—separating the heads (first distillate containing volatile compounds), hearts (the desirable middle portion), and tails (final distillate with heavier compounds). Taking only the best portion of the hearts creates smoother, cleaner flavor. Regional variations emerge from differences in water sources, secondary grains (some add wheat, rye, or barley), and family techniques passed through generations. Commercial products labeled as moonshine aim to recreate these characteristics through similar ingredients and production methods. For more about the history and evolution of moonshine, you can explore moonshine in Appalachia.

How did moonshiners avoid getting caught during Prohibition?

Appalachian moonshiners developed elaborate strategies to evade law enforcement throughout the Prohibition era and beyond. Remote locations provided the first line of defense, with stills hidden in dense forest, caves, or hollows accessible only by unmarked trails known to locals. Operations often employed lookouts—sometimes children too young to face serious charges—who used complex signaling systems (bird calls, positioned items, or later, CB radios) to warn of approaching strangers. Many moonshiners operated only at night (hence “moonshine”), using blackout methods to hide telltale smoke or light. Still design evolved to minimize detectability, with underground furnaces, camouflaged equipment, and even underwater condensation systems that eliminated visible steam.

When transportation became necessary, moonshiners modified vehicles with powerful engines, enhanced suspension systems, and hidden compartments—innovations that would later influence stock car racing. Sophisticated social networks provided further protection, with community members refusing to cooperate with “revenuers” even when they weren’t directly involved in production. Some operations maintained political protection through strategic relationships with local law enforcement or government officials, sometimes facilitated by regular payments or free product. These combined strategies allowed thousands of stills to operate throughout Prohibition, supplying not just local communities but major urban markets hundreds of miles from production sites.

Where can I legally taste authentic Appalachian moonshine today?

Legitimate distilleries throughout the Appalachian region now produce authentic moonshine using traditional methods while complying with modern regulations. For the most immersive experiences, visit distilleries in eastern Tennessee, western North Carolina, and southwestern Virginia—regions with the strongest historical connections to moonshine production. Many offer tours explaining traditional methods and modern adaptations, followed by guided tastings of both unaged white whiskey and flavored varieties. Some notable operations include Ole Smoky and Sugarlands in Tennessee, Call Family Distillers and Howling Moon in North Carolina, and Belmont Farm and Five Mile Mountain in Virginia—all with direct connections to moonshining families.

For deeper historical context, combine distillery visits with stops at regional museums featuring moonshine exhibits. The Museum of Appalachia in Clinton, Tennessee, the Blue Ridge Institute in Ferrum, Virginia, and the Mountain Gateway Museum in Old Fort, North Carolina all maintain extensive collections of historic stills, photographs, and artifacts. Some heritage sites occasionally offer demonstrations of traditional methods using authentic equipment (operating under special educational permits), providing glimpses of production techniques without actually producing consumable spirits.

For those seeking the fullest understanding of moonshine heritage, consider visiting during regional festivals that celebrate mountain traditions. Events like the Carolina Moonshine Heritage Festival in North Wilkesboro or the Virginia Mountain Moonshine Jamboree feature educational programs, music, and opportunities to meet distillers with direct connections to historical production. These combined experiences offer comprehensive introduction to the technical, cultural, and historical dimensions of Appalachian moonshine tradition.