Moonshine Production Techniques: Expert Tips for Better Flavor and Yield

Key Takeaways: Better Moonshine, Bigger Yields

- Temperature control during mashing (particularly maintaining 152°F for optimal enzyme activity) can dramatically increase your sugar conversion and final alcohol yield.

- The quality of your ingredients directly influences flavor – using proper proportions of flaked maize, malted barley, and quality water makes a significant difference.

- Making precise cuts during distillation separates the difference between harsh, potentially dangerous moonshine and a smooth, clean spirit.

- Fermentation management is crucial – allowing full completion (7-10 days) until the mash tastes dry rather than sweet ensures maximum alcohol production.

- Proper equipment and safety protocols aren’t just recommendations – they’re essential for both quality production and preventing serious hazards.

The art of moonshine production has evolved from backwoods necessity to a craft pursuit for many home distillers. Whether you’re looking to perfect your technique or just starting out, understanding the fundamental principles behind creating exceptional spirits will transform your results. The difference between mediocre and remarkable moonshine often comes down to precision, patience, and attention to detail at each stage of the process.

While commercial distilleries have industrial equipment and generations of expertise, home distillers can achieve comparable results by mastering key techniques that professionals use. These methods aren’t complicated, but they do require understanding the science behind fermentation and distillation. By following the guidelines in this article, you’ll be able to produce moonshine with cleaner flavors, higher yields, and more consistent results than you thought possible in a home setting.

Why Most Home Distillers Fail at Making Great Moonshine

“Ole Smoky Moonshine Flavors Ranked” from www.mashed.com and used with no modifications.

The path to exceptional moonshine is littered with common mistakes that plague even enthusiastic distillers. Rushing the process stands as perhaps the most prevalent error – cutting corners during fermentation, making hasty cuts during distillation, or skipping temperature monitoring can all result in subpar spirits. Many beginners also fall into the trap of using low-quality ingredients, particularly when it comes to water and grains, not realizing how dramatically these choices impact the final product. Another critical mistake is improper sanitation, which introduces unwanted bacteria that create off-flavors that no amount of distillation can fully remove.

Quality Ingredients: The Foundation of Exceptional Moonshine

“Sippin’ Saint Moonshine – Burnt Church …” from burntchurchdistillery.com and used with no modifications.

Every great batch of moonshine begins with thoughtfully selected ingredients. The character of your final spirit is directly influenced by what goes into your mash. While recipes vary, understanding the role each component plays allows you to make intentional choices rather than blindly following formulas. Traditional moonshine recipes have been refined over generations for good reason – they create a balanced foundation of flavors that distill beautifully.

Selecting the Perfect Grains for Your Mash

The grain bill for traditional moonshine typically centers around corn (flaked maize), which provides the sweet, distinctive character that defines classic American moonshine. The standard proportion hovers around 80% corn, with the remaining 20% usually being malted barley. Malted barley contributes vital enzymes that convert starches to fermentable sugars, making it an essential component even in corn-heavy recipes. For more complexity, some distillers incorporate small amounts of rye or wheat – rye adds a spicy character, while wheat contributes a smoother, bread-like quality. For more tips on crafting your moonshine, check out this guide on how to make moonshine.

Quality matters tremendously – freshly milled grains provide significantly better flavor than pre-ground products that may have oxidized. Many experienced distillers recommend flaked maize over whole corn because it gelatinizes more easily during cooking, making the starches more accessible to enzymes. When selecting grains, look for products specifically intended for brewing or distilling rather than feed-grade materials, which may contain additives or inconsistent quality.

The traditional recipe calling for 9 pounds of flaked maize and 2 pounds of malted barley for a 6.75-gallon batch creates an ideal balance that converts efficiently while producing characteristic moonshine flavor. This ratio has stood the test of time because it maximizes both yield and flavor when properly processed. For those looking to enhance their brew, exploring how to make moonshine taste smooth can provide valuable insights.

Water Quality and Its Impact on Flavor

Water constitutes the majority of your mash by volume, making its quality paramount to your final product. Municipal water often contains chlorine and chloramines that can create medicinal off-flavors, while well water may have high mineral content that affects fermentation. The best practice is using filtered water that removes contaminants while maintaining a moderate mineral profile – completely distilled water actually lacks minerals yeast need for healthy fermentation. If using tap water, allowing it to stand overnight helps dissipate chlorine, though chloramines require filtration through activated carbon to be removed effectively.

Yeast Selection: The Unsung Hero of Fermentation

Yeast selection impacts both flavor development and alcohol yield more than many beginners realize. While bread yeast can ferment sugar into alcohol, distiller’s yeasts are specifically cultivated for higher alcohol tolerance, cleaner fermentation, and complementary flavor development. Turbo yeasts promise quick, high-alcohol fermentations but often produce harsher spirits with more congeners compared to slower-working distiller’s yeasts. The difference becomes particularly noticeable in the final product – proper distiller’s yeast creates fewer fusel alcohols and unwanted compounds that can create headaches and rough flavors. For traditional corn-based moonshine, a whiskey yeast strain that enhances grain character while tolerating higher alcohol levels (around 14-18% ABV) strikes the ideal balance between efficiency and flavor quality.

Sugar Types and How They Affect Your Final Product

Many modern moonshine recipes incorporate sugar to boost alcohol content, but the type of sugar and amount used significantly impacts your results. Plain white granulated sugar ferments cleanly but contributes little flavor, while brown sugar or molasses adds complexity at the cost of potentially longer fermentation times. Sugar should complement rather than overwhelm your grain bill – adding too much creates a thin-tasting spirit lacking the rich character that defines quality moonshine. A good rule of thumb for traditional recipes is limiting sugar additions to about 20-30% of the total fermentables, allowing the grain character to remain dominant while still achieving desired alcohol levels. Remember that pushing your mash beyond your yeast’s alcohol tolerance threshold simply wastes sugar that won’t convert, potentially creating a stuck fermentation.

One advanced technique used by experienced distillers involves staggered sugar additions – adding portions of sugar throughout fermentation rather than all at once at the beginning. This approach reduces osmotic pressure on yeast cells, often resulting in more complete fermentation and higher final alcohol content without creating excess stress that leads to off-flavors. For a traditional corn moonshine, this might mean starting with your grain mash, then adding half your sugar after primary fermentation begins, and the remainder when activity starts to slow. To explore more about the cultural roots of this practice, check out moonshining traditions.

Mastering the Mash: Temperature Control Secrets

“The Smoothest Moonshine Mash Recipe You …” from stillntheclear.com and used with no modifications.

Temperature control during mashing is perhaps the single most critical factor in determining your moonshine’s quality and yield. The mashing process converts grain starches into fermentable sugars through enzymatic action, but these enzymes operate within specific temperature ranges. Precise temperature management ensures maximum conversion efficiency, directly impacting how much alcohol your yeast can produce during fermentation. Many beginners underestimate the importance of maintaining these temperatures throughout the entire mashing period, resulting in incomplete conversion and reduced yields.

Investing in a quality digital thermometer with fast read times makes temperature monitoring significantly easier and more accurate. Traditional floating thermometers can be off by several degrees, and when enzymes have specific temperature requirements, those degrees matter tremendously. For those serious about consistency, temperature-controlled electric brewing systems eliminate much of the guesswork and manual adjustment needed with stovetop methods.

Optimal Cooking Temperatures for Different Grain Bills

Different grains gelatinize at different temperatures, which is crucial to understand when creating your mash. Corn requires the highest heat, needing to reach approximately 190°F to fully break down its starchy structure. Barley, wheat, and rye have lower gelatinization temperatures ranging from 145-155°F. When working with a traditional corn-heavy recipe, you’ll need to start with a high temperature approach for the corn, then cool to the enzyme-active range before adding your malted barley.

A proper cooking procedure for a traditional corn mash starts with heating your water to approximately a 165°F before slowly stirring in your flaked maize. Gradually increase the temperature to 190°F while continuously stirring to prevent scorching. Hold at this temperature for about 20-30 minutes to ensure complete gelatinization before cooling to the critical enzyme range. This sequence unlocks the full potential of your grains and sets the stage for maximum conversion.

The 152°F Sweet Spot for Enzyme Activity

The most crucial temperature range in your entire process is between 148-158°F, with 152°F being the ideal target for balanced enzyme activity. At this temperature range, both alpha and beta amylase enzymes present in malted barley work efficiently to convert starches into fermentable sugars. Alpha amylase breaks complex starches into shorter chains, while beta amylase converts these chains into simple sugars yeast can ferment. Too high (above 158°F) and you’ll denature the beta amylase, resulting in less fermentable wort. Too low (below 145°F) and conversion becomes inefficiently slow.

Maintaining this temperature consistently for 60-90 minutes requires attention and occasionally adding small amounts of heat. Many distillers wrap their mash tun in blankets or use insulated vessels to hold temperature more effectively. The difference between a mash held perfectly at 152°F for an hour versus one that fluctuated significantly can be as much as 15-20% in final alcohol yield – a massive difference that directly affects your output. For more insights into traditional methods, explore moonshining traditions.

Cooling Techniques That Preserve Flavor

After conversion is complete, rapidly cooling your mash to fermentation temperature (usually 70-80°F) prevents bacterial contamination and preserves the fermentable sugars you’ve worked hard to create. Every minute your mash spends above 120°F after conversion increases the risk of bacterial contamination and undesirable flavors. Immersion chillers made of copper coils connected to cold water sources can drop temperatures quickly without diluting your mash. For smaller batches, an ice bath works effectively, though it takes longer and requires monitoring.

One often overlooked technique is pre-chilling a portion of your water (about 20% of total volume) and adding it after conversion is complete. This approach requires calculating your final volumes in advance but can significantly reduce cooling time without specialized equipment. Always ensure your cooling method maintains sanitation – introducing contaminants at this stage can ruin an otherwise perfect mash.

Fermentation: Where the Magic Happens

“The Basics of Making Moonshine with …” from copperholic.com and used with no modifications.

Fermentation transforms your sweet mash into an alcoholic wash ready for distillation, but this complex biological process requires careful management to achieve optimal results. During fermentation, yeast consumes sugars and produces alcohol, carbon dioxide, and flavor compounds that significantly impact your final product. While it might seem like a waiting game, active management during this stage can dramatically improve both yield and flavor quality of your moonshine.

Many beginners treat fermentation as the simple part of moonshine production, but professional distillers know that careful management during this stage sets the foundation for everything that follows. Proper fermentation management begins with pitching an appropriate amount of healthy yeast into properly temperature-controlled mash and continues through monitoring and maintaining optimal conditions throughout the entire process. This attention to detail during fermentation often separates exceptional moonshine from merely acceptable results.

Ideal pH Levels for Maximum Yield

The pH of your mash directly impacts yeast performance, with the optimal range falling between 5.2-5.5 for most distiller’s yeasts. Too acidic (below 5.0) or too alkaline (above 6.0) stresses the yeast, resulting in slower fermentation, lower alcohol yields, and potential off-flavors. Testing pH before pitching yeast using inexpensive pH strips allows you to make adjustments if needed. For mashes that are too alkaline, small additions of food-grade acid (like lactic acid) can bring pH into the optimal range. For overly acidic mashes, calcium carbonate (chalk) can safely raise pH without adding unwanted flavors.

Water chemistry plays a significant role in starting pH, and different grain bills naturally produce different pH levels during mashing. Corn-heavy mashes tend to have higher pH levels than those containing more barley or rye. Monitoring pH throughout fermentation also provides valuable information – a steady pH indicates healthy fermentation, while rapid drops may signal bacterial infection requiring immediate attention.

Temperature Management Throughout Fermentation

Yeast activity generates heat, which can push fermentation temperatures higher than optimal levels, especially in larger batches. Most distiller’s yeasts perform best between 75-80°F, though specific strains have different preferences. Temperatures above 85°F stress the yeast, producing more fusel alcohols that contribute harsh flavors and potential hangovers. Conversely, temperatures below 65°F can cause sluggish fermentation that may stall before completing. Active cooling methods like fermenter jackets filled with water or wet towels wrapped around fermenters can help maintain ideal temperatures during peak activity.

The temperature profile throughout fermentation also impacts flavor development. Some distillers intentionally start at the lower end of the acceptable range (around 70°F) and allow the temperature to naturally rise through fermentation, believing this creates more complex flavor development. Others maintain strict temperature control throughout the entire process for consistency across batches. Both approaches can produce excellent results when executed with attention to detail and appropriate equipment.

Signs Your Fermentation Is Complete (And When to Stop Waiting)

Complete fermentation typically takes 7-10 days for a traditional moonshine mash, though variables like temperature, yeast strain, and nutrient availability can extend or shorten this timeframe. The most reliable indicators of completion include: cessation of bubbling activity for at least 24 hours; a specific gravity reading that remains unchanged for consecutive days; and a noticeably drier taste with minimal sweetness remaining. Moving to distillation before fermentation fully completes leaves fermentable sugars unconverted, reducing your alcohol yield. Conversely, waiting too long after completion can allow unwanted bacterial activity to develop, potentially creating off-flavors.

A common mistake among beginners is rushing this stage based on calendar timing rather than fermentation indicators. Different recipes and conditions can significantly affect fermentation duration – a nutrient-rich environment with ideal temperatures might complete in 5 days, while cooler temperatures or higher starting gravity could extend the process to 14 days or more. Patience and observation during this stage pay dividends in both yield and flavor quality in your final product.

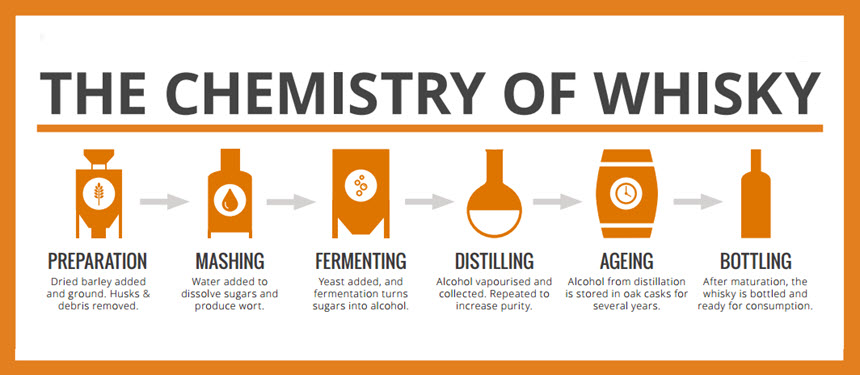

Distillation Techniques That Boost Flavor and Purity

“The Chemistry Behind The Whisky We Love …” from www.distillerytrail.com and used with no modifications.

Distillation separates alcohol from your fermented wash, but it’s far more nuanced than simply boiling and collecting the results. The distillation process allows you to selectively capture the compounds that contribute to pleasant flavors while leaving behind those that create harshness or potential danger. Mastering distillation techniques gives you precise control over your moonshine’s character, purity, and potency. This is where art meets science in moonshine production, with small adjustments in technique creating dramatically different results.

The fundamental principle behind distillation is that different compounds evaporate at different temperatures, allowing you to separate them based on their respective boiling points. Ethanol (the desirable alcohol) boils at 173°F, while water boils at 212°F. However, numerous other compounds exist in your fermented wash, including methanol, acetone, various esters, fusel alcohols, and congeners – all of which vaporize at different temperature points. Understanding these differences allows you to make intentional choices about what to keep and what to discard during the distillation run.

- Foreshots (first 5% of the run): Contains methanol and other dangerous compounds – always discard

- Heads (next 30% of alcohol collected): Contains acetone, aldehydes, and lighter compounds – mostly discard

- Hearts (middle 30-40% of alcohol): The cleanest, purest portion with balanced flavors – keep entirely

- Tails (final 25-35% of alcohol): Contains fusel alcohols and heavier compounds – selectively keep

The temperature control during distillation directly influences the separation of these compounds. Running your still too quickly forces compounds together, while a properly managed, slow distillation allows for cleaner separation between the different fractions. This is why many experienced distillers focus heavily on maintaining specific temperature ranges and collection rates throughout their runs rather than simply collecting everything that comes off the still.

While commercial distilleries use sophisticated equipment to monitor and control these variables precisely, home distillers can achieve excellent results with careful attention to detail and consistent techniques. The difference between mediocre and exceptional moonshine often comes down to patience during the distillation process and making careful cuts between the different fractions rather than equipment sophistication.

The Critical First Cut: Removing Foreshots Properly

The foreshots constitute approximately the first 5% of your total distillate collection and contain methanol and other highly volatile compounds that are not only unpleasant but potentially dangerous. Always discard this fraction completely, regardless of how efficiently you want to run your still. For a 5-gallon wash, this typically means discarding the first 2-3 ounces of distillate that comes off your still. The foreshots often have a distinctive sharp, solvent-like smell that’s noticeably different from the later fractions. For more insights on distillation practices, explore moonshining traditions that have been passed down through generations.

Temperature readings during distillation can help identify when you’ve moved beyond the foreshots, though vapor temperature is a better indicator than wash temperature. Foreshots typically come off at temperatures below 172°F (vapor temperature), while the transition to heads occurs as the temperature stabilizes closer to ethanol’s boiling point. Some distillers collect the foreshots separately not for consumption but for cleaning purposes or as fuel for alcohol burners, as these compounds make effective solvents.

Addressing Low Alcohol Content Issues

When your moonshine comes out weaker than expected, the problem typically stems from incomplete fermentation or inefficient distillation. First, check your fermentation process – did you allow it to complete fully? Hydrometers don’t lie – if your final gravity reading was higher than 1.000-1.010, residual sugars remained unconverted. Consider using yeast nutrients in future batches to ensure your yeast can process all available sugars. Temperature control during fermentation is equally critical – too cold and the yeast becomes sluggish; too hot and it may die off prematurely.

Solving Cloudy Distillate Problems

Cloudy moonshine indicates the presence of oils, proteins, or other compounds that should have been left behind during proper distillation. The most common cause is running your still too rapidly, which causes “puking” – where the wash boils violently and carries unwanted compounds into your distillate. Always maintain a gentle, controlled boil throughout your run. Another culprit is collecting too far into the tails, where fusel oils and other heavier compounds begin coming through.

For already-cloudy moonshine, a second distillation at a very slow rate often clears the problem. Alternatively, filtering through activated carbon can remove many impurities, though this may also strip away some desirable flavors. Some traditional moonshiners simply allow the spirit to rest for several weeks, as many oils will naturally separate and can be carefully decanted away from the clear spirit. For more insights, discover why moonshine needs to sit before it reaches its full potential.

- Run your still more slowly to prevent wash from entering the column

- Make sure your column packing (if using one) is properly installed

- Consider a second, slower distillation run for troublesome batches

- Filter through activated carbon as a last resort

- Allow time for natural settling and carefully decant the clear portion

Prevention is always better than correction – maintaining proper distillation temperatures and flow rates typically eliminates cloudiness issues entirely. Experienced distillers aim for about 2-3 drops per second during the hearts collection phase rather than a steady stream, which allows for better separation of compounds and cleaner final spirits. For those interested in learning more about aging techniques, exploring the best barrels for aging moonshine can be beneficial.

Dealing with Stuck Fermentation

A stuck fermentation occurs when yeast activity stops prematurely, leaving unconverted sugars and lower alcohol content than expected. Common causes include nutrient deficiency, temperature fluctuations, excessive sugar content creating osmotic pressure, or pH drift outside the optimal range. To restart a stuck fermentation, first check the temperature and bring it back to the optimal 75-80°F range. Then create a “starter” with fresh, active yeast in a small amount of diluted, room-temperature mash before gradually adding it to your main fermentation vessel. Adding a small amount of yeast nutrient can often provide the missing elements your exhausted yeast needs to finish the job. In extreme cases, adding a high-alcohol-tolerant yeast strain like EC-1118 (champagne yeast) can power through where other strains have given up.

Safety First: Non-Negotiable Practices

“Safety first Stock Photos, Royalty Free …” from depositphotos.com and used with no modifications.

Safety concerns in moonshine production aren’t overblown – they represent real risks that must be respected. Historical incidents of blindness, poisoning, fires, and explosions associated with illicit distillation occurred because producers lacked proper knowledge and equipment. Today’s home distiller has access to information and materials that dramatically reduce these risks, but only when properly implemented. No batch of moonshine, regardless of quality, is worth risking your health or safety. The following sections outline non-negotiable safety practices that should be incorporated into every production run.

Methanol Dangers and How to Avoid Them

Methanol (wood alcohol) represents the most serious health concern in spirits production, capable of causing blindness or death even in small amounts. It forms naturally in fruit-based fermentations and to a lesser degree in grain fermentations. The key to safety is understanding that methanol vaporizes before ethanol, which means it concentrates in the foreshots (first portion of your distillation run). Always discard the first 100-150ml per 5 gallons of wash regardless of how efficiently you want to run your still. Never attempt to increase yield by keeping these initial distillates. The characteristic “nail polish remover” smell of the foreshots is a clear indicator of compounds you don’t want in your final product. The good news is that grain-based traditional moonshine recipes produce very little methanol naturally, making them inherently safer than fruit-based washes when proper distillation techniques are followed.

Fire Hazard Prevention

Alcohol vapors are extremely flammable, creating genuine fire risks during distillation. Always operate your still in an area free from open flames, sparks, or heating elements that could ignite escaped vapors. Use electric heating sources rather than open flames when possible, and ensure all electrical connections are properly grounded and kept away from potential liquid spills. Keep a properly rated fire extinguisher (Class B for flammable liquids) within immediate reach of your distillation area. Never leave a running still unattended, as temperature fluctuations or boilovers can quickly create dangerous situations. Perhaps most importantly, ensure all connections in your still are sealed properly to prevent vapor leaks – using flour paste for traditional setups or proper gaskets and clamps for modern equipment.

Proper Ventilation Requirements

Adequate ventilation isn’t just about comfort – it’s essential for preventing dangerous accumulation of alcohol vapors and carbon dioxide. Distillation should always occur in a well-ventilated space with good air exchange, ideally with windows or doors that can be opened to provide fresh air. For indoor operations, consider installing a ventilation fan that exhausts directly outdoors. Carbon dioxide produced during fermentation is heavier than air and can accumulate at floor level, potentially creating an asphyxiation hazard in enclosed spaces. This is particularly important when fermenting in basements or other below-grade locations. The test is simple: if you feel lightheaded or notice unusual smells accumulating in your production area, your ventilation is inadequate and needs immediate improvement. For more tips on improving your moonshine process, check out this moonshine yeast review.

Beyond the immediate safety concerns, proper ventilation also helps regulate temperature in your distillation area. Overheated spaces not only create uncomfortable working conditions but can affect the precision of your distillation process. Consistent ambient temperatures allow for more accurate monitoring of your still’s performance and more predictable results in your final product.

Take Your Moonshine from Amateur to Expert Level

“Master Distiller …” from www.youtube.com and used with no modifications.

The difference between amateur and expert-level moonshine often comes down to attention to detail across the entire production process. Expert distillers keep meticulous notes on every batch, tracking ingredients, temperatures, times, and results to refine their process incrementally. This scientific approach to an age-old craft allows for systematic improvements rather than relying on memory or chance. Begin documenting every aspect of your process, particularly noting which techniques produce your preferred flavor profiles and yields.

Consider developing a signature recipe that you refine over multiple batches. While experimenting with different grain bills and techniques is educational, mastering one specific style allows you to detect subtle improvements more effectively than constantly changing multiple variables. Many renowned distilleries became famous by perfecting a single distinctive style rather than producing many adequate variations. Your signature moonshine might feature a specific grain ratio, a particular fermentation temperature profile, or a distinctive aging technique that sets it apart from commercial products.

Finally, invest in quality equipment that matches your production goals. While good moonshine can be made with basic setups, precision instruments eliminate variables and allow you to focus on technique. A quality thermometer, accurate hydrometer, proper fermentation vessel with airlock, and well-designed still appropriate for your preferred style will yield dividends in consistency and quality. Remember that the still is merely a tool – the real expertise lies in how you use it through each phase of production.

Frequently Asked Questions

New distillers often share common questions about moonshine production. While the craft has room for personal preference and style, certain technical aspects have clear best practices based on chemistry and generations of experience. The following questions address some of the most common areas of confusion for those developing their distillation skills.

Beyond these specific questions, remember that successful moonshine production combines scientific precision with artisanal judgment. Measuring instruments provide data, but developing the sensory skills to evaluate your product by appearance, aroma, and taste remains equally important. The best distillers balance quantitative measurements with qualitative assessment throughout their process. For instance, knowing how to make moonshine taste smooth can greatly enhance the quality of your final product.