What Temp Do You Run a Still At: Complete Guide for Beginners

Key Takeaways

- The optimal temperature for running a still ranges from 78°C to 82°C (172°F to 180°F) for collecting the hearts (best quality spirits), with variations based on still type and desired spirit.

- Different distillation phases require different temperature ranges: foreshots (below 78°C/172°F), heads (78-82°C/172-180°F), hearts (82-94°C/180-201°F), and tails (above 94°C/201°F).

- Temperature measurement location matters significantly – column temperature gives the most accurate readings for making collection decisions.

- Still type dramatically affects optimal operating temperatures – pot stills typically run hotter (80-95°C) than reflux stills (78-82°C).

- Proper temperature control is the key difference between producing premium spirits and potentially dangerous or unpalatable alcohol.

Temperature control is the cornerstone of successful distillation. Whether you’re crafting whiskey, vodka, or moonshine, understanding and maintaining the right temperature will make the difference between a smooth, flavorful spirit and something potentially undrinkable or even dangerous. The temperature at which you run your still isn’t just a technical detail—it’s the primary tool for separating the good from the bad, and the great from the merely good.

The Science Behind Distillation Temperatures

“What is the Distillation Process? | The …” from www.chemicals.co.uk and used with no modifications.

Distillation works on a simple principle: different compounds evaporate at different temperatures. By controlling temperature precisely, distillers can separate the desirable compounds from the undesirable ones. This temperature-based separation is why distillation has been used for centuries to create everything from perfumes to spirits.

Why Temperature Control Makes or Breaks Your Spirits

Temperature control is arguably the most critical aspect of distillation. Run your still too cold, and nothing happens. Run it too hot, and you’ll collect everything at once, defeating the purpose of distillation. The sweet spot allows you to collect ethanol (the good alcohol) while leaving behind fusel oils, methanol, and other compounds that can cause hangovers or worse. Precise temperature management also lets you capture the aromatic compounds that give spirits their distinctive character. Most seasoned distillers will tell you that learning to “read” and respond to temperature changes during a run is what separates novices from masters.

Every degree matters when you’re aiming for quality. A temperature difference of just 2-3°C can dramatically change what’s coming out of your still. This is why professional distillers invest in high-quality thermometers and monitoring systems. They understand that consistent temperature control leads to consistent product quality, which is the foundation of any successful distillery.

Temperature Control Impacts:

• Flavor profile of the final spirit

• Safety of the product (methanol separation)

• Efficiency of the distillation process

• Consistency between batches

• Overall yield of usable spirit

Ethanol’s Boiling Point: The Magic Number

The cornerstone of alcohol distillation is understanding that ethanol (drinking alcohol) boils at 78.37°C (173.1°F), while water boils at 100°C (212°F). This difference in boiling points is what makes distillation possible. When heating a fermented wash containing both water and alcohol, the ethanol vaporizes first, allowing you to collect it separately.

However, this textbook number doesn’t tell the whole story. In practice, you’ll rarely see exactly 78.37°C on your thermometer during distillation. That’s because you’re not distilling pure ethanol—you’re distilling a solution of ethanol, water, and various flavor compounds. This mixture creates what chemists call an “azeotrope,” which affects the boiling temperature.

Additionally, atmospheric pressure affects boiling points. At higher elevations where atmospheric pressure is lower, your ethanol will boil at slightly lower temperatures. For every 300 meters (1,000 feet) above sea level, subtract about 1°C (1.8°F) from the standard boiling point.

How Alcohol Percentage Affects Boiling Temperature

The relationship between alcohol concentration and boiling temperature is one of the most practical pieces of knowledge for distillers. As alcohol percentage increases, the boiling point decreases. A wash with 5% ABV (alcohol by volume) will start boiling at a higher temperature than a wash with 10% ABV. For more insights into distillation, check out the difference between spirits and moonshine.

This relationship creates a temperature curve during distillation. When you first start collecting, the temperature will be lower because you’re collecting mostly alcohol. As the run progresses and the alcohol percentage in the boiler decreases, the temperature gradually rises. By monitoring this temperature rise, experienced distillers can make precise cuts between different fractions without even tasting or smelling the output.

| Alcohol % in Boiler | Approximate Boiling Point | What’s Coming Out |

|---|---|---|

| 40-20% | 78-82°C (172-180°F) | Heads/Early Hearts |

| 20-10% | 82-89°C (180-192°F) | Hearts |

| 10-5% | 89-94°C (192-201°F) | Late Hearts/Early Tails |

| <5% | 94-100°C (201-212°F) | Tails |

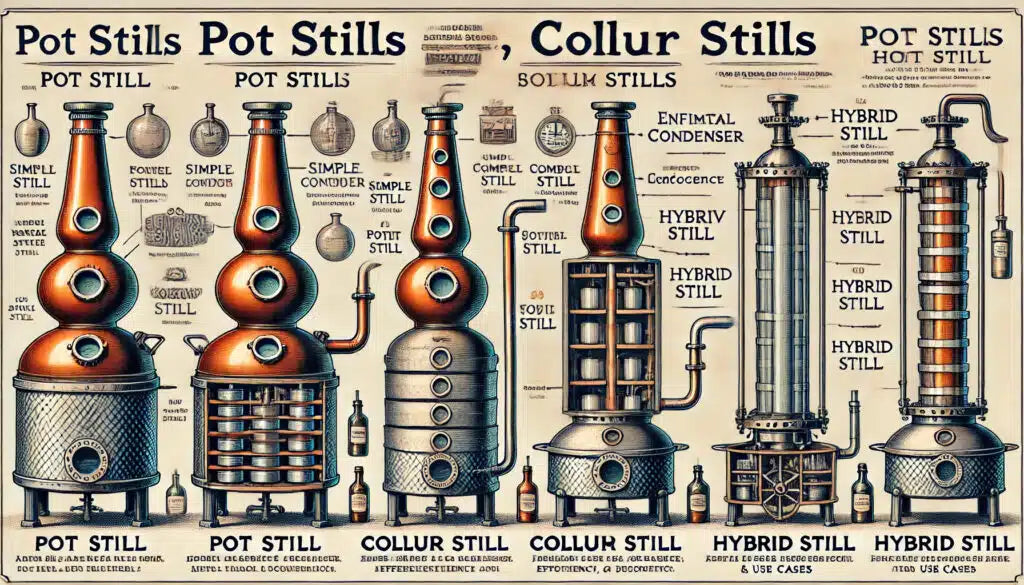

Temperature Targets for Different Still Types

“Alcohol Distillation – Brewcraft” from www.brewcraft.co.za and used with no modifications.

Not all stills are created equal, and each type has its own optimal temperature range. Understanding what temperatures work best for your specific still design will help you maximize both efficiency and quality in your distillation runs. The three main still types—pot, reflux, and column—each have distinct temperature profiles that experienced distillers learn to work with.

Pot Still Temperature Ranges (80°C-95°C)

Pot stills are the traditional workhorses of the distilling world, used for centuries to create flavorful spirits like whiskey, rum, and brandy. These stills operate at relatively higher temperatures compared to other designs, typically between 80°C and 95°C (176°F to 203°F). The higher temperature range is due to the pot still’s simple design, which provides less separation between compounds.

When running a pot still, you’ll notice the temperature rises steadily throughout the run. You might start collecting around 80°C (176°F) and continue until about 95°C (203°F), at which point you’re well into the tails. This wider temperature range is actually an advantage for flavor-forward spirits, as it allows more congeners (flavor compounds) to come through in the final product.

Reflux Still Temperature Sweet Spots (78°C-82°C)

Reflux stills are the precision instruments of the distilling world, designed to create high-proof, neutral spirits. They operate in a much tighter temperature band than pot stills, typically between 78°C and 82°C (172°F to 180°F). This narrow range is by design—reflux stills use additional cooling to create internal reflux, which increases separation and purity.

When running a reflux still, temperature stability is crucial. Your goal is to maintain the column temperature as close to 78.3°C (173°F) as possible for maximum ethanol purity. Even a 2°C increase can significantly change what compounds are coming over. Most experienced reflux distillers control their heat source to maintain temperature within a 1°C margin, often using digital controllers for precise management.

The key to successful reflux distillation is patience. Allow the still to equilibrate at temperature before making any adjustments, and make small, incremental changes to your heat input. A common mistake among beginners is constantly adjusting the heat, which prevents the still from reaching equilibrium and results in inconsistent output. For more insight, you might want to explore the three main parts of a still to better understand its operation.

Column Still Temperature Management

Column stills combine elements of both pot and reflux stills and offer the most versatility in terms of temperature control. With multiple plates or sections, column stills allow for different temperatures at different heights within the column. The bottom section might be at 95°C (203°F) while the top section sits at 78°C (172°F). To understand more about the components of a still, you can read about what is the onion head on a still.

This temperature gradient is what gives column stills their remarkable efficiency. By controlling the temperature at each plate or section, distillers can precisely control which compounds make it to the condenser. Professional distilleries often monitor temperatures at multiple points throughout the column to ensure optimal operation.

For beginners with column stills, focus on the temperature at the top of the column near the condenser. This is your most important measurement and should generally be kept between 78°C and 82°C (172°F to 180°F) for collecting hearts. As you gain experience, you can experiment with manipulating temperatures at different points in the column to achieve specific flavor profiles. For a deeper understanding of the components involved, check out the three main parts of a still.

Step-by-Step Temperature Guide Through a Distillation Run

“Simple Distillation | GCSE Chemistry …” from www.shalom-education.com and used with no modifications.

Understanding how temperatures change throughout a complete distillation run will help you anticipate what’s happening inside your still. Each phase has its own temperature signature, and learning to read these changes will make you a more effective distiller. Let’s walk through a typical run from start to finish.

Heating Phase: Getting Started Right

The heating phase is all about patience. Apply heat gradually to avoid scorching and to allow your still to warm evenly. During this phase, you’ll see the temperature in your boiler rise steadily from room temperature up toward the boiling point of alcohol. For most wash compositions (5-10% ABV), you’ll start seeing vapor production when the boiler reaches about 70-75°C (158-167°F).

A common mistake is applying too much heat too quickly. This can cause the wash to foam or “puke” into the column, contaminating your distillate. Aim for a heating rate of about 5-10°C (9-18°F) per 15 minutes. This slow, steady approach gives the still time to establish proper vapor paths and equilibrium.

When you first see condensation beginning in your condenser (usually around 75-78°C/167-172°F in the column), reduce your heat slightly to maintain control. This is the moment when your still transitions from heating to active distillation, and you want this transition to be smooth and controlled.

Foreshots and Heads Collection Temperatures

Foreshots begin coming over at around 50-65°C (122-149°F) in your collection vessel, though your column temperature will likely read closer to 75-78°C (167-172°F). These initial distillates contain acetone, methanol, and other volatile compounds you want to discard. Never consume foreshots – they are used for cleaning or discarded safely.

As the temperature stabilizes around 78-79°C (172-174°F) at the top of your column, you’ll transition into the heads portion of your run. Heads contain ethanol mixed with lighter, more volatile compounds that can cause headaches. While not as dangerous as foreshots, heads are often set aside for redistillation or discarded. For a typical 5-gallon wash, expect to collect about 100-200ml of foreshots and heads combined, though this varies based on your wash composition and still design.

Hearts Collection: The Perfect Temperature Zone

The hearts—your premium drinking alcohol—typically begin when the column temperature stabilizes between 78-82°C (172-180°F), though this can vary slightly based on your still design and wash composition. For pot stills, the temperature range for hearts collection is wider, typically 82-89°C (180-192°F). This is where temperature monitoring becomes critical for making proper cuts. To understand more about the components of a still, you can read about the three main parts of a still.

During hearts collection, maintain a steady heat input to keep your temperature as stable as possible. Dramatic temperature fluctuations during this phase will result in inconsistent quality. Your drip rate should be slow and steady—aim for 1-3 drops per second for optimal separation. As your run progresses through hearts, you’ll notice the temperature slowly climbing, often by just a few tenths of a degree every 15-20 minutes. This gradual rise is normal and indicates that the alcohol percentage in your wash is decreasing.

For beginners, it’s helpful to make small collections (100-200ml each) throughout the hearts run and label them with the corresponding temperature. This allows you to taste and evaluate each fraction separately once they’ve been properly diluted, helping you learn what temperatures produce the flavors you prefer in your specific still setup.

Tails Temperature Indicators

The transition to tails is signaled by a more noticeable increase in temperature, typically above 89-94°C (192-201°F) for pot stills or above 82°C (180°F) for reflux stills. This temperature jump corresponds with a shift in the flavor profile—from the clean, pleasant hearts to the oilier, sometimes musty tails. The distillate will begin to develop a cloudy appearance when mixed with water, and the smell changes from sweet and clean to more cereal-like or vegetative.

Cooling Down Safely

- Turn off heat source completely before handling any part of the still

- Maintain cooling water until vapor production has completely stopped

- Allow all metal parts to cool to touch before disassembly or cleaning

- Never add fresh wash to a hot still

- Store collected distillate in glass containers away from heat sources

Proper cooling is just as important as proper heating. When ending your run, first turn off your heat source completely while maintaining water flow through your condenser. A sudden stop in cooling water while the still is hot can cause pressure buildup and potential safety hazards. Continue running cooling water until you can comfortably place your hand on the boiler without feeling heat. For more detailed information on distillation temperatures, you can explore additional resources.

Many beginners make the mistake of rushing the cooldown process or disassembling the still while it’s still warm. This can expose you to hot vapor or surfaces. A proper cooldown also prevents thermal shock to glass components and extends the life of gaskets and seals.

Once completely cooled, drain your boiler immediately to prevent leftover mash from drying and creating difficult-to-remove deposits. This simple maintenance step will make your next distillation run much easier to prepare for.

Temperature Measurement: Tools and Techniques

“Moonshine Still Condenser or Brew Pot …” from www.amazon.com and used with no modifications.

- Digital probe thermometers: Accuracy of ±0.5°C, instant readings, often waterproof

- Infrared thermometers: Non-contact measurement, good for surface temperatures

- Dial thermometers: Traditional option, requires no batteries, typically ±2°C accuracy

- Temperature controllers: Automated systems that maintain set temperatures

- Wireless monitoring systems: Allow remote tracking of still temperatures

Quality temperature measurement is the foundation of successful distillation. Professional distillers recommend investing in at least two temperature monitoring devices—one for the boiler and one for the column/head. For beginners, digital probe thermometers offer the best balance of accuracy, ease of use, and affordability. Look for models with temperature ranges from 0-100°C (32-212°F) with 0.1°C resolution for the most precise readings. To understand more about the components involved, you might want to learn about the three main parts of a still.

Infrared thermometers, while convenient, have limitations in distillation applications. They only measure surface temperatures, which can differ significantly from internal vapor temperatures. They’re useful for quick checks but shouldn’t be your primary measurement tool. If you do use an infrared thermometer, be aware that shiny metal surfaces can give inaccurate readings due to reflected infrared radiation.

Accuracy matters tremendously in distillation. Even a 1-2°C deviation can shift what compounds you’re collecting. Before your first run, calibrate your thermometers by measuring boiling water (which should read 100°C/212°F at sea level) and making note of any offset. Apply this correction factor to your readings during distillation.

Temperature controllers represent the next level of precision. These devices can maintain your heat source at exactly the level needed to hold your still at the desired temperature. While not necessary for beginners, they become invaluable as you progress and seek more consistency between runs.

Where to Place Your Thermometer

Thermometer placement can dramatically affect your readings and distillation decisions. The most valuable temperature reading comes from the top of your column, just before the condenser. This position tells you exactly what’s vaporizing at that moment, helping you make accurate cuts between foreshots, heads, hearts, and tails. Some distillers drill specific ports for thermometer probes, while others use specialized fittings that incorporate temperature measurement. To understand more about the components involved, learn about the three main parts of a still.

Boiler temperature readings are less useful for making cuts but provide valuable information about your overall run progress. If you’re monitoring boiler temperature, place your thermometer so it measures the vapor space above the liquid, not the liquid itself. The liquid temperature will always read higher than the vapor temperature and won’t accurately reflect what’s coming over in your distillate. For the most comprehensive monitoring setup, measure temperatures at both the boiler and the column head simultaneously.

Digital vs. Analog Thermometers for Distilling

Digital thermometers offer superior precision for distillation, with most quality models providing readings to 0.1°C accuracy. This level of detail matters when you’re trying to identify the transition points between different fractions, particularly the crucial shift from heads to hearts. Digital thermometers also respond faster to temperature changes, giving you more immediate feedback on how your adjustments affect the still’s operation. For beginners, I recommend starting with a good digital thermometer that can withstand the humid conditions around a still.

Analog thermometers, while traditional, typically only offer 1-2°C precision and slower response times. However, they have the advantage of not requiring batteries and generally being more durable in hot, steamy environments. If you opt for an analog thermometer, choose one designed specifically for distillation with a range of 0-110°C (32-230°F) and a stem long enough to reach properly into your vapor path. Many experienced distillers keep both types on hand—digital for precision measurement and analog as a reliable backup.

Temperature Monitoring Systems Worth the Investment

As you advance in your distilling journey, consider upgrading to more sophisticated temperature monitoring systems. Multi-point digital systems allow you to simultaneously track temperatures at different locations throughout your still, giving you a complete picture of the thermal dynamics during your run. These systems typically display real-time data and often include logging capabilities so you can review temperature patterns after your run is complete. The insights gained from this comprehensive monitoring can help you fine-tune your process and achieve more consistent results.

Wireless monitoring systems represent the cutting edge of distillation technology, allowing you to track temperatures remotely via smartphone or computer. This capability is particularly valuable for long runs where constant attention to the still isn’t practical. Some advanced systems can even send alerts when temperatures reach specific thresholds, letting you know when it’s time to make cuts or when a problem might be developing. While these systems require a larger initial investment, they quickly pay for themselves through improved efficiency and product quality.

Temperature Profiles for Popular Spirits

“How To Do a Stripping Run With Your …” from brewhaus.com and used with no modifications.

Different spirits require different temperature approaches to achieve their characteristic flavors and profiles. Understanding these variations will help you tailor your distillation process to create exactly the spirit you’re aiming for, whether it’s a robust whiskey or a clean, neutral vodka. To get started, you might want to explore a traditional corn-based moonshine recipe that can guide you through the basics of distillation.

Whiskey Distillation Temperatures

Whiskey distillation typically operates at higher temperatures to preserve the grain-derived flavors that give this spirit its character. On a pot still, whiskey distillers often collect hearts between 82-88°C (180-190°F), accepting some of the heavier congeners that would be excluded in cleaner spirits. This temperature range captures the vanilla, caramel, and wood notes that develop during aging, while still excluding the harshest fusel oils that emerge above 90°C (194°F). The best whiskey distillers maintain a slow, steady temperature increase throughout the hearts collection, allowing for precise separation of desirable and undesirable compounds.

For double distillation whiskey processes, the first distillation (often called the “stripping run”) is typically performed quickly and at higher temperatures, while the second, more careful distillation focuses on the critical 80-90°C (176-194°F) range where most of the desirable flavors reside. Temperature rises more quickly in whiskey distillation compared to vodka, and experienced distillers use this rate of change to inform their cuts as much as the absolute temperature readings.

Vodka’s Temperature Requirements

Vodka demands the strictest temperature control of any spirit, with successful distillation requiring you to maintain column temperatures very close to the theoretical 78.3°C (173°F) boiling point of ethanol. This tight control, often within 1°C, ensures the highest purity by preventing heavier congeners from rising into the condensation path. Multi-stage or reflux distillation is common for vodka, with each stage operating at progressively narrower temperature bands to achieve the neutral character vodka is known for.

The goal with vodka distillation is temperature stability rather than progression. While whiskey distillers expect and work with gradually rising temperatures, vodka distillers aim to hold their still at the ethanol boiling point for as long as possible. This requires careful heat management and often necessitates more precise equipment, including temperature controllers that can automatically adjust heat input to maintain the target temperature. For home distillers, vodka production offers an excellent opportunity to develop temperature management skills that will benefit all future distilling endeavors.

Rum and Brandy Temperature Considerations

Rum and brandy distillation falls between whiskey and vodka in terms of temperature approach, typically operating in the 80-86°C (176-187°F) range for hearts collection. These fruit-based spirits benefit from preserving certain flavor-carrying esters that contribute to their distinctive profiles. Temperature progression is particularly important for rum, as the traditional pot still distillation captures different flavor compounds as the temperature gradually increases throughout the run. For a deeper understanding of these processes, you can explore more about distillation temperatures.

The molasses-based wash used for rum contains numerous volatile compounds that emerge at different temperatures. By carefully monitoring temperature increases and making strategic cuts, rum distillers can capture the light, floral notes at lower temperatures while still incorporating some of the heavier, caramel-like compounds that emerge as temperatures rise. Brandy distillers similarly use temperature profiles to capture the essence of the base fruit, often distilling at slightly lower temperatures than whiskey to preserve delicate fruit aromatics while still developing enough body for aging.

Common Temperature Problems and Solutions

“Caution sign Images – Free Download on …” from www.freepik.com and used with no modifications.

Even experienced distillers encounter temperature-related challenges. Recognizing these common issues and knowing how to address them can save your batch and improve your distilling skills. Most temperature problems fall into three categories: fluctuation, excessive heat, or insufficient heat.

Fluctuating Temperatures: Causes and Fixes

Temperature fluctuations during distillation typically indicate inconsistent heat input or issues with your cooling system. These variations can blur the lines between different fractions, making clean cuts difficult and resulting in inconsistent product quality. The most common causes include unstable heat sources (particularly gas burners affected by pressure fluctuations), inconsistent cooling water temperature or flow, and drafts affecting the still. To resolve fluctuations, first check that your heat source is stable and appropriately sized for your still—electric elements often provide more consistent heat than gas burners for smaller stills. For more information on distillation and its legal aspects, you can read about stills legality in the US.

Next, examine your cooling system, ensuring water flow remains constant throughout your run. Installing a simple flow meter can help identify variations that might not be visible to the eye. Consider insulating your column and condenser lines to prevent ambient temperature variations from affecting your readings. For serious distillers, investing in a PID (Proportional-Integral-Derivative) temperature controller represents the ultimate solution, as these devices automatically adjust your heat source to maintain target temperatures regardless of external conditions.

Too Hot: Preventing Scorching and Off-Flavors

Excessive temperatures create multiple problems, including scorched wash, carried-over solids, and collection of unwanted compounds. When wash temperatures exceed 95°C (203°F) at the boiler base, proteins and sugars can burn onto heating elements, creating acrid flavors that taint your entire batch. This scorching often occurs when heat is concentrated in a small area rather than distributed evenly throughout the boiler. To prevent this, use a diffuser plate with direct-fired stills or consider a heat exchanger design where hot water or oil surrounds the boiler rather than applying heat directly. For more insights on still components, explore what is the onion head on a still.

If temperatures are too high in your column, you’re likely applying too much power too quickly. The solution is to reduce your heat input and allow the still to equilibrate before making additional adjustments. Remember that distillation is a marathon, not a sprint—patience with temperature management yields superior results. For electric heating elements, consider installing a variable power controller rather than relying on simple on/off switches. This allows for fine-tuning heat input to maintain optimal temperatures throughout your run.

Too Cold: How to Maintain Proper Heat

Insufficient temperature can stall your distillation run or result in extremely slow production. If your still struggles to reach proper operating temperature, first check for heat losses through insufficient insulation. Wrapping your boiler and column with heat-resistant insulation material can dramatically improve efficiency and help maintain proper temperatures. Pay particular attention to the connection between your boiler and column, as this junction often allows significant heat escape.

Another common cause of low temperatures is undersized heating elements or burners. As a general guideline, aim for approximately 1000-1500 watts of heating power per 5 gallons (19 liters) of wash for efficient operation. If you’re operating in a cold environment, you may need additional power or insulation to compensate. Finally, check for cooling water that’s too cold or flowing too rapidly through your condenser, as this can create excessive reflux and prevent proper temperature development in your column. Adjusting cooling water flow is often the simplest solution to temperature issues in the upper portions of your still.

Temperature Safety Protocols Every Distiller Must Know

“Holding Temperatures Label Decal …” from www.amazon.com and used with no modifications.

Temperature management isn’t just about product quality—it’s fundamentally about safety. Distillation involves flammable vapors and hot equipment, creating potential hazards that must be managed through proper temperature protocols. Never compromise on these safety measures, as the consequences of temperature-related accidents can be severe. To understand more about the equipment involved, learn about the three main parts of a still.

Fire Hazards and Prevention

Alcohol vapors become increasingly flammable as temperatures rise, with the greatest risk occurring between 78°C and 100°C (172°F and 212°F)—precisely the range in which distillation takes place. To prevent fires, always ensure your distillation area is well-ventilated and free from ignition sources. This means no open flames, sparking electrical equipment, or smoking anywhere near your still during operation. For electric stills, use explosion-proof heating elements and controls designed specifically for distillation applications.

Monitor boiler temperatures carefully to prevent overheating, which can create excessive vapor pressure and potential leaks of flammable vapor. Never exceed 100°C (212°F) in your boiler, as this indicates all alcohol has been removed and further heating only creates unnecessary risk. Keep appropriate fire extinguishers (rated for alcohol fires) within reach, and never leave a running still unattended. Remember that temperature management is your first line of defense against distillation-related fires.

Vapor Management at Different Temperatures

Different temperature ranges produce vapors with varying levels of flammability and toxicity. The foreshots fraction, which distills at the lowest temperatures (below 78°C/172°F at column head), contains the highest concentration of methanol and other harmful compounds. These vapors require careful management, including proper ventilation and complete separation from any product intended for consumption.

Emergency Shutdown Procedures

Every distiller should establish and practice emergency shutdown procedures for temperature-related problems. If temperatures exceed safe levels or you observe any signs of leaking vapor, immediately cut heat to the still while maintaining cooling water flow. Do not attempt to move or disassemble the still until it has completely cooled. In case of fire, use appropriate fire extinguishing methods (class B extinguisher) and evacuate the area if the fire cannot be immediately controlled. For more information on safety, you might want to explore the legality of stills in the US.

Document your emergency procedures and post them visibly in your distilling area. Practice these procedures regularly so they become automatic responses rather than panic-driven reactions. Remember that proper temperature monitoring and control is the best way to avoid emergencies in the first place, but being prepared for worst-case scenarios is an essential part of responsible distilling.

Master Your Still Through Temperature Control

“Tradition in Contemporary Craft Spirits …” from compassohio.com and used with no modifications.

Temperature mastery is the defining skill that separates casual distillers from craftsmen. By developing a deep understanding of how temperature affects every aspect of the distillation process, you gain precise control over your final product. The journey to temperature mastery begins with careful measurement and observation, progresses through experimentation with different parameters, and culminates in the ability to consistently produce high-quality spirits through intuitive temperature management.

- Keep detailed temperature logs for every run, noting when different fractions begin and end

- Practice making small, incremental heat adjustments and observing their effects

- Experiment with different temperature ranges for the same recipe to identify optimal profiles

- Learn the specific temperature signatures of your particular still setup

- Invest in increasingly precise temperature monitoring equipment as your skills advance

The best distillers develop an almost symbiotic relationship with their still, anticipating temperature changes before they occur and making proactive adjustments. This level of mastery comes only through experience, but the journey itself is rewarding. Each batch teaches you something new about temperature dynamics, building your skills incrementally until temperature management becomes second nature.

Remember that while guidelines and numbers are helpful starting points, every still setup has unique thermal characteristics that you’ll need to discover through hands-on experience. The temperature readings that signal perfect hearts collection on my still might be slightly different on yours. By combining technical knowledge with personal experience, you’ll develop temperature intuition specific to your equipment and processes.

Frequently Asked Questions

After teaching countless distilling workshops and fielding questions from beginners, I’ve compiled these most common temperature-related questions. Understanding these fundamentals will help you avoid common pitfalls and accelerate your distilling expertise.

What exactly happens if my still temperature gets too high?

When still temperatures exceed optimal ranges, several negative consequences occur. First, you’ll collect a higher proportion of fusel oils and tannins, resulting in harsh flavors and potential headaches for consumers. Second, excessive temperatures can cause foaming or “puking” where the wash carries over into your condenser, contaminating your distillate. Finally, very high temperatures increase fire risks and can damage equipment, particularly gaskets and seals. The quality impact is most significant—high temperatures blur the separation between hearts and tails, making it impossible to achieve clean, smooth spirits.

Can I use any thermometer for measuring still temperatures?

Standard kitchen thermometers are insufficient for distillation due to limited temperature ranges, poor accuracy, and materials that may not withstand distillation conditions. For proper distillation, use thermometers specifically rated for the full distillation range (0-110°C/32-230°F), with accuracy of at least ±1°C. Thermometer materials matter too—stainless steel probes resist corrosion from alcohol vapors, while glass thermometers risk breaking and contaminating your batch. Digital brewing/distilling thermometers offer the best combination of accuracy, durability, and value for beginners.

How do I adjust temperatures for high-altitude distilling?

Altitude Adjustment Table for Distillation Temperatures

Altitude Water Boiling Point Ethanol Boiling Point (approx) Hearts Collection Range Sea Level 100°C (212°F) 78.3°C (173°F) 78-82°C (172-180°F) 1,000 ft (305m) 99°C (210.2°F) 77.4°C (171.3°F) 77-81°C (171-178°F) 5,000 ft (1524m) 95°C (203°F) 73.9°C (165°F) 74-78°C (165-172°F) 8,000 ft (2438m) 92.2°C (198°F) 71.4°C (160.5°F) 71-75°C (160-167°F)

Altitude significantly affects distillation temperatures because atmospheric pressure decreases at higher elevations, lowering the boiling points of all liquids. For every 1,000 feet (305 meters) above sea level, ethanol’s boiling point decreases by approximately 1°C (1.8°F). This means that if you’re distilling at 5,000 feet elevation, your target column temperature for hearts collection would be around 73-77°C (163-171°F) rather than the sea-level 78-82°C (172-180°F). For more information, you can refer to this guide on distillation temperatures.

To calibrate your process for high-altitude distilling, first establish your local water boiling point by heating water and recording its stable boiling temperature. The difference between this reading and 100°C (212°F) tells you how much to adjust your target distillation temperatures. For example, if water boils at 95°C (203°F) in your location, subtract 5°C (9°F) from all standard distillation temperature targets.

Remember that altitude affects not just boiling points but also cooling efficiency. At higher elevations, your condenser may need colder water or increased flow rates to achieve the same cooling effect as at sea level. Monitor your output temperature carefully and adjust cooling accordingly to maintain proper condensation.

The good news is that while the temperatures change with altitude, the relative relationships between different fractions remain consistent. The transition from heads to hearts to tails still occurs in the same sequence and with similar temperature progressions, just at lower absolute values.

Why does my temperature keep rising during hearts collection?

A gradual temperature rise during hearts collection is normal and expected as the alcohol concentration in your wash decreases throughout the run. When you begin distilling, your wash might contain 8-10% alcohol, which boils at a lower temperature than water. As you remove this alcohol through distillation, the remaining mixture in your boiler contains progressively less alcohol and more water, causing the boiling point to rise. This temperature increase is actually a useful indicator of your progress through the run and helps signal the transition from hearts to tails.

Is it normal for temperature to fluctuate during distillation?

Minor temperature fluctuations of 0.5-1.0°C are normal during distillation, particularly with manual heat sources. However, rapid or large fluctuations (more than 2°C) indicate problems that need addressing. Stable temperatures produce consistent quality, while fluctuations blur the distinctions between different fractions. The goal should be to maintain temperatures within a 1°C range during critical collection periods, particularly during the transition from heads to hearts.

Temperature stability improves with experience and equipment quality. Electronic controllers, insulation, and proper still design all contribute to more stable operating temperatures. If you’re experiencing significant fluctuations, systematically eliminate potential causes including drafts, inconsistent heat sources, cooling water temperature variations, and improper thermometer placement.

Remember that temperature stability is particularly important during hearts collection, where even small fluctuations can affect flavor profiles. During foreshots and late tails collection, larger fluctuations are less critical since these fractions are typically discarded or segregated for redistillation.

With practice, you’ll develop a feel for your particular still’s normal temperature behavior and quickly recognize when something isn’t working as expected. This temperature intuition becomes one of your most valuable distilling skills, allowing you to produce consistent, high-quality spirits batch after batch.

When distilling, it’s crucial to understand the appropriate temperatures for different stages of the process. This ensures that you are collecting the right components and maximizing the quality of your distillate. If you’re new to this, you might want to check out this guide on distillation temperatures to help you get started.