Why Do You Throw Out The First Batch Of Moonshine?

Key Takeaways

- The first runnings of moonshine (foreshots) contain methanol which can cause blindness or death if consumed – always discard them completely.

- For safety, discard approximately the first 30mL per 5L batch (about 2-5% of total volume) to eliminate most dangerous compounds.

- Methanol has a lower boiling point (148.5°F) than ethanol (173.1°F), which is why it comes out first during distillation.

- Professional distillers use a scientific approach when making cuts between distillation phases for both safety and flavor reasons.

- Regeneration Distilling recommends never consuming homemade spirits without proper knowledge and equipment to test for methanol content.

Discarding the first portion of moonshine isn’t just an old wives’ tale – it’s a critical safety measure that separates experienced distillers from dangerous amateurs. When that first clear liquid starts dripping from your still, it carries compounds that can permanently blind or even kill you. Understanding why this tradition exists could save your life or someone else’s.

The practice of throwing out the “foreshots” has deep roots in distilling culture, but it’s backed by hard science rather than superstition. Regeneration Distilling, experts in traditional spirits production, emphasize that proper separation techniques are non-negotiable for anyone attempting to produce safe, quality spirits at home.

The Dangerous Truth About Moonshine’s First Runnings

“History of Moonshine | Cool Material” from coolmaterial.com and used with no modifications.

The first liquid that emerges during distillation isn’t the prized moonshine you’re hoping to enjoy. Instead, these initial runnings, called foreshots, contain concentrated methanol and other volatile compounds that boil off before the desirable ethanol. This isn’t a matter of preference or flavor – it’s about preventing serious harm. No amount of aging, filtering, or flavoring can make foreshots safe to consume.

Methanol Poisoning Can Cause Blindness or Death

When methanol enters the body, it’s metabolized by the liver into formaldehyde and formic acid – compounds that attack the central nervous system with devastating effects. The initial symptoms resemble ordinary alcohol intoxication, making it particularly dangerous. As little as 10mL of pure methanol can cause permanent blindness, while 30mL can be lethal. Unlike ethanol’s hangover, methanol poisoning can progress to respiratory failure, coma, and death within 24-48 hours if untreated.

The First 30mL Per 5L Batch Contains Most Toxins

For home distillers working with a typical 5-liter batch, the first 30mL (about 1 fluid ounce) contains the highest concentration of methanol and other harmful compounds. This seemingly small amount represents roughly 2-5% of your total yield but removing it dramatically increases safety. Commercial distillers use precise measurements and sometimes chemical analysis, but home distillers should err on the side of caution by discarding more rather than less. Remember that you can’t identify methanol by smell, taste, or appearance – it looks and smells nearly identical to ethanol. For more insights on traditional practices, explore moonshining traditions.

“The difference between drinking shine and going blind comes down to respecting the first cut. When in doubt, throw it out.” – Traditional distiller wisdom

Safety Must Come Before Taste When Distilling

While flavor is important, it should never override safety concerns when distilling spirits at home. Many novice moonshiners make the dangerous mistake of trying to maximize yield by keeping too much of the early runnings. The potential cost of this error far outweighs the benefit of a slightly larger batch. Professional distillers understand that making proper cuts is both a science and an art, but safety always takes precedence over all other considerations.

What Are Foreshots and Why They’re Toxic

“How Safe Is Moonshine? What You Need to …” from missouripoisoncenter.org and used with no modifications.

Foreshots are the very first liquid that comes out of your still during distillation. This fraction contains the highest concentration of low-boiling-point compounds, primarily methanol but also including acetone, various aldehydes, and other volatile chemicals. These substances evaporate at temperatures lower than ethanol, which is why they emerge first in the distillation process. No traditional or modern distiller would ever consider these compounds part of their finished product.

Methanol vs Ethanol: The Critical Difference

Methanol and ethanol are chemical cousins that look and smell almost identical, but their effects on the human body couldn’t be more different. Ethanol is the drinking alcohol we desire in spirits, while methanol is a toxic industrial solvent. The primary structural difference is that ethanol has two carbon atoms while methanol has only one. This seemingly small variation makes methanol metabolize into compounds that attack the optic nerve and central nervous system. For more on the dangers of methanol, you might explore traditional moonshining traditions where safe practices are crucial. What makes this especially dangerous is that initial intoxication feels similar, potentially delaying treatment until severe damage occurs.

Other Harmful Compounds in Early Distillate

While methanol gets most of the attention, it’s not the only dangerous substance found in foreshots. Acetone (the active ingredient in nail polish remover), various aldehydes, and esters also come through early in the distillation process. These compounds contribute to the harsh, solvent-like aroma characteristic of foreshots and can cause severe headaches, nausea, and organ damage when consumed. Even in small amounts, these chemicals create that infamous “paint thinner” quality that ruins both the drinking experience and your health.

The combination of these volatile organic compounds makes the first portion of distillate particularly hazardous. Industrial distillers use sophisticated equipment to analyze and separate these compounds, but home distillers must rely on careful technique and conservative safety margins to ensure their product is safe.

Real-Life Consequences of Methanol Poisoning

The dangers of methanol aren’t theoretical. Numerous outbreaks of methanol poisoning have occurred worldwide, typically when unscrupulous producers skip proper distillation techniques or when inexperienced distillers make critical mistakes. In 2019, dozens of people in India died after consuming contaminated moonshine. Similar incidents have occurred in the United States, Eastern Europe, and throughout developing nations where regulation is minimal. Survivors often face permanent blindness, neurological damage, and lifelong health complications from a single drinking session.

The Science of Distillation Fractions

“Science PNG, Vector, PSD, and Clipart …” from pngtree.com and used with no modifications.

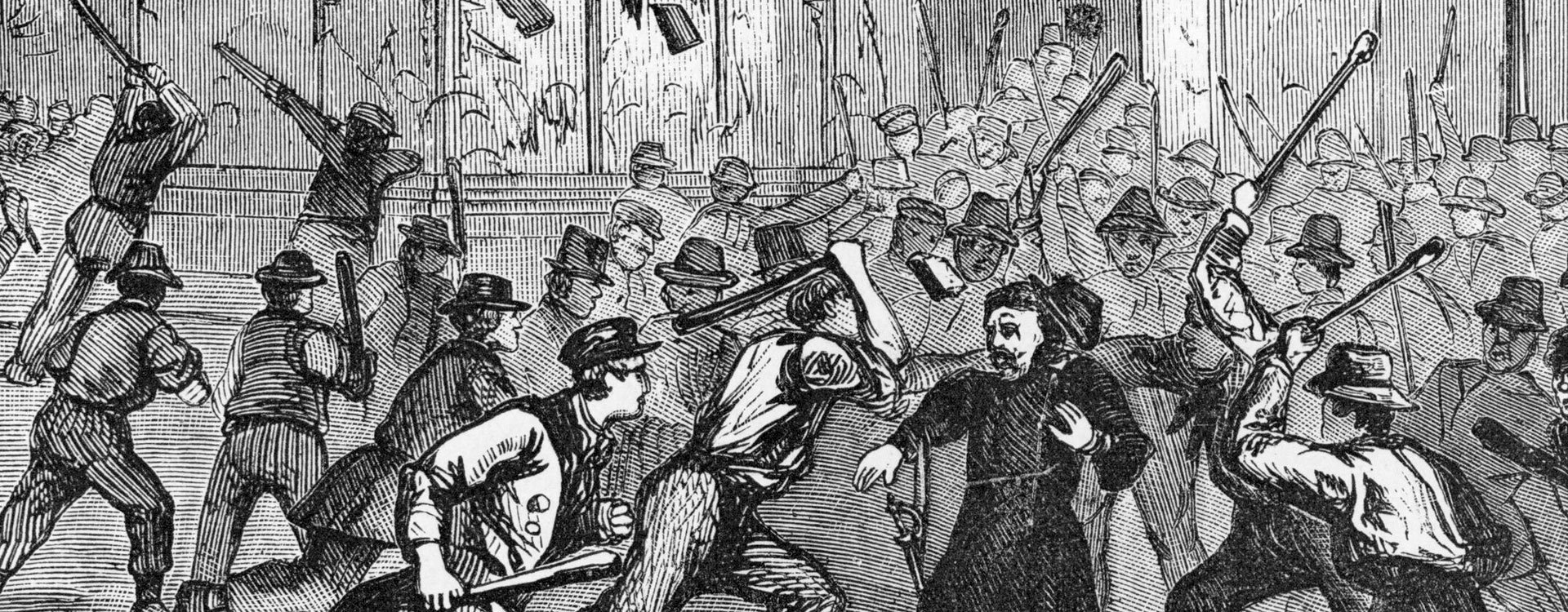

Understanding the science behind distillation helps explain why proper separation of fractions is essential. Distillation works by heating a fermented liquid to create vapor, then cooling that vapor to recondense it into liquid form. Different compounds vaporize at different temperatures, allowing for separation based on their boiling points. This fundamental principle enables distillers to isolate and remove harmful substances while concentrating the desirable ethanol.

The art of distillation lies in knowing exactly when each phase begins and ends. Commercial operations use precise instrumentation, but traditional moonshiners rely on temperature readings, aroma assessment, and generations of passed-down knowledge to make these critical decisions.

Boiling Points Determine What Comes Out When

The key to understanding distillation cuts is recognizing that different compounds have different boiling points. Methanol boils at approximately 148.5°F (64.7°C), while ethanol boils at about 173.1°F (78.4°C). This temperature difference, though seemingly small, allows for separation during careful distillation. Water, with its higher boiling point of 212°F (100°C), comes through later in the process. By monitoring temperature and controlling heat input, a skilled distiller can make precise cuts between these different fractions.

Why Methanol Always Comes Out First

Methanol emerges first during distillation precisely because it has the lowest boiling point of the significant compounds in your mash. As your still heats up, methanol vaporizes before ethanol, creating a concentrated pocket of methanol in the first portion of your distillate. This scientific reality is why the traditional practice of discarding the first runnings developed long before modern chemistry could explain the phenomenon.

In a properly fermented wash made from grains or fruits, methanol is present in small amounts – but the distillation process concentrates it in the foreshots. Without proper separation, this concentrated methanol makes its way into the final product, creating serious health risks for consumers. This is why even commercial distilleries carefully separate and discard these initial runnings, despite the loss of overall yield.

The Four Phases: Foreshots, Heads, Hearts, and Tails

A complete distillation run produces four distinct fractions, each with different characteristics and purposes. Foreshots come first and contain the highest concentration of methanol and other toxic compounds – these must always be discarded. Heads follow the foreshots and contain less methanol but still have harsh, volatile compounds that contribute to hangovers and off-flavors – experienced distillers often set these aside for redistillation. Hearts are the prized middle cut, containing mostly ethanol with desirable flavor compounds and minimal impurities. Tails emerge last as the still temperature rises, bringing through heavier compounds and fusel oils that contribute both interesting flavors and potential off-notes.

Learning to identify these four phases is fundamental to producing safe, high-quality spirits. While foreshots are always discarded for safety reasons, the treatment of heads and tails varies depending on the distiller’s goals and the specific spirit being produced. Some whiskey makers keep portions of the tails for their rich, complex flavors, while vodka producers aim for the purest hearts fraction possible.

How to Safely Discard the First Runnings

“How to Make Moonshine : 4 Steps (with …” from www.instructables.com and used with no modifications.

When discarding foreshots, err on the side of caution and use conservative estimates. The consensus among experienced distillers is that foreshots typically represent about 2-5% of your total expected yield. For a 5-gallon mash that might produce 1 gallon of spirit, you should discard at least the first 60-150ml without exception. This initial liquid should be immediately segregated and marked as hazardous waste – never store it near consumable products or in food containers.

The safest approach is to collect these foreshots in heat-resistant glass containers and allow them to cool completely before disposal. Some distillers use foreshots as a cleaning solution or fuel for alcohol lamps, but never for consumption or skin contact. If disposing of foreshots, treat them as you would other household chemicals – check local regulations for proper disposal methods.

Exact Measurements for Different Batch Sizes

Knowing exactly how much to discard varies with batch size. For a standard 5-gallon mash that might yield around 1 gallon (3.8L) of distillate, you should typically discard the first 150-200mL without exception. For smaller batches, scale accordingly – about 30-40mL per gallon of wash is a good rule of thumb. Commercial distillers working with larger volumes often discard a higher percentage because the concentration of methanol in the initial output can be greater due to more efficient stills.

The exact volume also depends on your still design. Pot stills generally produce less concentrated foreshots than column stills, potentially requiring more volume to be discarded to ensure all methanol is removed. When using a reflux still with higher separation efficiency, the foreshots will be more concentrated but occupy a smaller volume of the total output.

- 5-gallon wash: Discard first 150-200mL

- 10-gallon wash: Discard first 300-400mL

- 25-gallon wash: Discard first 750-1000mL

- 50-gallon wash: Discard first 1.5-2L

Using Temperature as Your Guide

Temperature monitoring provides another reliable method for identifying when foreshots end. Since methanol boils at approximately 148.5°F (64.7°C) and ethanol at 173.1°F (78.4°C), the still head temperature offers valuable guidance. Most distillers consider the foreshots complete when the head temperature reaches about 175-178°F (79-81°C), indicating that ethanol is now the primary component coming through. However, temperature alone isn’t foolproof – always combine it with volume measurements and sensory evaluation.

A quality digital thermometer inserted at the top of your still column provides the most accurate readings. The temperature will plateau temporarily when transitioning between foreshots and heads as the still shifts from primarily methanol to primarily ethanol vapor. This plateau can help identify the transition point, though experienced distillers will still discard well past this mark for safety.

Equipment for Testing and Separation

Professional distillers utilize specialized equipment to make precise cuts. A proofing parrot allows continuous monitoring of alcohol strength, while collection vessels marked in small increments help track volumes accurately. Glass collection jars rather than plastic are preferred, as they don’t impart flavors and allow clear visual assessment of the distillate. Some distillers use small mason jars to collect spirits in 100mL increments during critical transition phases, allowing for precise blending later.

While laboratory equipment for methanol detection exists, it’s rarely practical for home distillers. Instead, focus on careful technique and conservative safety margins. Collecting distillate in small, sequential containers allows for tasting (once safely past the foreshots) and smelling to identify the transitions between phases. Never taste anything until you’ve well cleared the foreshots portion based on volume calculations.

Making Clean Cuts Between Distillation Phases

“Chemistry LibreTexts” from chem.libretexts.org and used with no modifications.

The art of making proper “cuts” between distillation phases requires both technical knowledge and sensory skill. These transitions aren’t abrupt – they occur gradually, with overlapping characteristics between adjacent phases. Professional distillers develop this skill over years of experience, learning to identify subtle changes in aroma, flavor, and mouthfeel that signal the transition points. For those looking to enhance their moonshine’s flavor, understanding how to make moonshine taste smooth can be an essential part of the process.

When to Switch from Foreshots to Heads

The transition from foreshots to heads represents the most critical safety decision in the distillation process. After discarding the calculated volume of foreshots, you’ll notice a gradual shift in the character of the distillate. The sharp, solvent-like aroma begins to soften, giving way to more alcoholic notes. While heads still contain some undesirable compounds, they’re primarily ethanol-based and not acutely toxic like foreshots. For more insights on the distillation process, you might want to explore the moonshining traditions that have shaped these practices.

Many distillers collect heads separately from hearts, setting them aside for redistillation in a future batch rather than including them in the current product. Heads typically run from about 175-185°F (79-85°C) still head temperature and have a distinctive nail polish remover quality that, while not dangerous in small amounts, contributes to hangovers and harsh flavor.

Finding the Sweet Spot: Heads to Hearts Transition

The transition from heads to hearts marks the beginning of your premium product. This shift occurs when the harsh, solvent-like qualities give way to cleaner, more pleasant aromas. The ethanol content remains high, typically around 160-170 proof (80-85% ABV), but without the harsh compounds from earlier fractions. You’ll notice the spirit becomes smoother on the palate with a cleaner finish – this is the “sweet spot” that distillers aim to capture. Learn more about methanol in moonshine and its effects.

This transition typically occurs when 15-30% of your total expected yield has been collected (including the discarded foreshots). Many craft distillers collect in small jars during this transition period, testing each to determine exactly where to make their cut. Temperature is less reliable here than sensory evaluation, as the still has largely stabilized at ethanol’s boiling point.

Hearts to Tails: Knowing When to Stop Collection

As distillation progresses, the hearts eventually transition to tails as ethanol becomes depleted and higher-boiling compounds start coming through. This transition is marked by dropping alcohol content, increasing oiliness, and the emergence of cereal, earthy, or sometimes sulfurous notes. The still head temperature will begin slowly climbing above 180°F (82°C), indicating that water and fusel oils are becoming more prevalent in the vapor.

The decision of how far into the tails to collect depends on your specific spirit goals. Whiskey makers often collect further into tails for the rich congeners that develop complexity during aging, while vodka producers cut early to maintain purity. For most beginners, stopping collection when the distillate reaches about 100-110 proof (50-55% ABV) provides a good balance. Beyond this point, the diminishing returns in alcohol content rarely justify the increasing presence of fusel oils and off-flavors.

Better Flavor Is a Bonus of Proper Separation

“Ole Smoky Tennessee White Chocolate …” from liquorama.com and used with no modifications.

While safety is the primary reason for discarding foreshots, proper separation techniques dramatically improve flavor quality as well. The harsh chemical notes from methanol and acetone create an unpleasant drinking experience even in non-toxic amounts. By making careful cuts, you’re not just producing safer spirits – you’re crafting a superior product with cleaner flavor and reduced hangover potential.

The Harsh Taste of Impure Spirits

Poorly separated spirits have a distinctive harshness that experienced drinkers immediately recognize. The presence of heads compounds creates a burning sensation beyond what the alcohol content would suggest, often accompanied by a sharp, acidic attack on the palate. These impurities contribute to the legendary reputation of bad moonshine – causing intense headaches, nausea, and that “feeling like death” the morning after. Even in non-toxic concentrations, these compounds create an inferior product that lacks the smooth character of properly distilled spirits.

Many of these harsh compounds have distinct aromas: acetone smells like nail polish remover, acetaldehyde has a green apple peel sharpness, and various esters contribute pungent, solvent-like qualities. Learning to identify these aromas helps distillers make better decisions about when to start collecting their hearts fraction.

How the “Hearts” Create Smooth Moonshine

The hearts fraction contains primarily ethanol along with the desirable flavor compounds that define your spirit’s character. This portion lacks the harsh volatiles from heads and the heavier oils from tails, creating a clean, smooth drinking experience. In properly distilled moonshine, you should taste the subtle grain notes from your mash, a clean alcoholic warmth, and none of the chemical harshness associated with poorly made spirits. The hearts, collected at 150-160 proof (75-80% ABV), can be diluted with pure water to drinking strength while maintaining this clean flavor profile.

Legal Considerations for Home Distillers

“Is Home Distilling Legal In My Country …” from distilmate.com and used with no modifications.

Before attempting any distillation, understand that producing spirits at home remains illegal in most jurisdictions without proper permits and tax payments. While knowledge about distillation safety is valuable, the information in this article is presented for educational purposes only. Regeneration Distilling reminds readers that unauthorized distillation can result in significant legal penalties including fines and imprisonment.

Federal Laws on Home Distillation

In the United States, federal law prohibits distilling spirits for beverage purposes without paying taxes and obtaining permits from the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau (TTB) and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). These regulations exist partly due to safety concerns – improperly produced spirits can cause serious harm. Unlike home brewing of beer or wine, which is legal in most states for personal consumption, spirits distillation faces stricter regulation due to both tax considerations and safety factors.

State Variations in Moonshine Regulations

State laws regarding distillation vary significantly. Some states have enacted craft distillery provisions that allow small-scale production under specific licensing requirements. Others maintain strict prohibitions with severe penalties. Several states like Kentucky, Tennessee, and Missouri have relaxed laws for small quantities produced for personal consumption, but these state exemptions don’t override federal prohibition.

For those interested in distillation, legal pathways exist through proper licensing or by participating in legal distillery workshops. Many craft distilleries offer educational programs where enthusiasts can learn distillation techniques under proper supervision while remaining on the right side of the law.

Stay Safe While Enjoying the Craft

“Drinking Moonshine …” from www.rachelsquiltpatch.com and used with no modifications.

The tradition of moonshine production carries deep cultural significance in many regions, representing independence, craftsmanship, and cultural heritage. By understanding the science behind safe distillation practices, you gain appreciation for the skill involved in producing quality spirits. Whether you’re a curious enthusiast or considering legal pathways into distillation, respect for proper technique and safety protocols remains essential. The best distillers combine generations of traditional knowledge with modern understanding of chemistry to create exceptional products that can be enjoyed without risk.

Remember that commercial spirits undergo rigorous testing and quality control to ensure safety. The separation of methanol and other harmful compounds isn’t just tradition – it’s a critical safety measure that legitimate producers never compromise. Regeneration Distilling encourages those interested in spirits production to pursue knowledge, respect tradition, and above all, prioritize safety in all aspects of the craft.

Frequently Asked Questions

The world of distillation contains many complexities, and beginners often have questions about safety, technique, and best practices. Below, we address some of the most common queries regarding the first runnings of moonshine and proper handling procedures.

Can I use the first batch for anything besides drinking?

The foreshots and early heads fractions have legitimate uses outside consumption. Many distillers collect these portions separately for use as cleaning solution, fuel for alcohol lamps, or as a solvent for tinctures not intended for consumption. Some traditional moonshiners use foreshots for treating minor external wounds as an antiseptic, though commercial alternatives are safer and more reliable. Remember that foreshots contain methanol and should never be used in any application involving ingestion, inhalation of vapors, or prolonged skin contact.

How can I tell if moonshine contains methanol without equipment?

Unfortunately, there’s no reliable way for consumers to detect methanol in spirits without specialized equipment. Methanol looks, smells, and initially tastes similar to ethanol, making it impossible to identify through casual sensory evaluation. The traditional flame test (checking if it burns blue) is unreliable as both methanol and ethanol produce similar colored flames.

The only reliable consumer protection is knowing your source. Commercial spirits are tested to ensure safety, while spirits from unknown sources carry significant risk. If you suspect methanol poisoning (unusual intoxication, visual disturbances, severe headache), seek immediate medical attention – early treatment can prevent permanent damage. For those interested in safer alternatives, you might explore infused moonshine recipes that can be made at home with proper guidance.

Is store-bought moonshine safe or do they remove the foreshots too?

Commercially produced “moonshine” sold in retail stores undergoes the same rigorous safety protocols as any other commercial spirit. These products are produced in regulated distilleries that properly separate and discard foreshots and harmful compounds. They’re subject to quality testing and must meet federal standards for methanol content (typically less than 0.1% by volume). The term “moonshine” on these products refers to the style and tradition rather than illicit production methods.

Legal commercial distilleries actually have more sophisticated equipment for making precise cuts than most illicit operations, typically resulting in a cleaner, safer product. They also face regular inspections and testing that ensure compliance with safety regulations.

Can I redistill bad moonshine to make it safer?

Redistillation cannot reliably remove methanol once it’s been mixed with the final spirit. The close boiling points of methanol and ethanol make complete separation extremely difficult without specialized equipment. If you suspect a spirit contains dangerous levels of methanol or other contaminants, redistillation is not a safe solution – discard the product entirely. For more information on the dangers of methanol in moonshine, you can read about methanol in the moonshine.

Some distillers do redistill the heads fraction (after properly discarding foreshots) to recover additional ethanol, but this requires proper equipment and technique. As a safety rule, never attempt to “fix” spirits of unknown quality or questionable origin through redistillation.

How much of my total batch should I expect to throw away?

Typical Discard Percentages by Fraction

Foreshots: 2-5% of total output (MUST always discard)

Heads: 20-30% of total output (Often collected separately for redistillation)

Hearts: 30-40% of total output (The premium product)

Tails: Remaining 25-40% (Partial collection depending on desired spirit)

The exact percentages vary based on your still design, mash composition, and desired final product. Column stills produce more defined fractions with clearer transition points, while pot stills create broader, more gradual transitions between phases. Most craft distillers aim to maximize the hearts collection while maintaining quality, which typically means keeping about 30-40% of the theoretical total yield for a single distillation run.

Ultimately, quality should always take precedence over quantity. Commercial operations can precisely calibrate their cuts to maximize yield while maintaining safety, but home distillers should prioritize wider safety margins at the expense of yield. No amount of additional product justifies compromising safety.

Understanding proper distillation techniques not only ensures safety but connects you to centuries of distilling tradition. The careful separation of distillate fractions represents the core craftsmanship that distinguishes fine spirits from dangerous imitations.

The knowledge of how to properly discard the first runnings of moonshine has likely saved countless lives throughout distillation history. What began as observation and tradition has been validated by modern chemistry, confirming the wisdom of generations of distillers who recognized the importance of this critical safety step.